GOLD FEVER

By 1830 approximately 14000 free settlers had decided to seek their fortunes in Australia, compared with the 63 000 convicts. This all changed in 1832 when the British government decided to finance working-class emigrants with some of the money gathered from land sales in Australia. The scheme was such a success that in the years between 1830 and 1850 Australia acquired another 173000 free settlers, together with 83 000 more convicts.

The squatter period

During the 1820’s, the people of New South Wales began to develop a strong economy based on the production of wool for export to Britain. The large profits that could be made from the wool trade encouraged more and more settlers to raise sheep for a living. But the government of New South Wales allowed settlers to buy or lease grazing land only within a limited area. All the land outside this area was considered government property. But by the mid-1820s the numbers of sheep had increased so greatly that, no matter what the government said, farmers set out with their flocks to find pastures on the grassy plains of the interior. Many settlers occupied government land illegally. These illegal landholders became known as squatters. When they came to land which had not been taken up, each man marked out his run (an outdoor enclosure for domestic animals), established his station (a sheep or cattle ranch) and claimed it as his own. Where, as often happened, there was no woman in the party, the men lived roughly, “half savage, half mad . . . half dressed, half not, unshaven, unshorn, shoes never cleaned, eating tea and damper1.” (M. Kiddle, Men of Yesterday, Melbourne University Press, 1061.)

In colonial Australia, stockmen (ковбои) developed the technique of making damper out of necessity. Often away from home for weeks, with just a camp fire to cook on and only sacks of flour as provisions, a basic staple bread evolved. It was originally made with flour and water and a good pinch (щепотка) of salt, kneaded (месить), shaped into a round, and baked in the ashes of the campfire or open fireplace.

Cooking the damper

Eventually the government had to recognize these squatters and in 1836 the Governor announced that anyone could squat on Crown lands on payment of 10 pounds a year license. The squatter’s flocks and herds increased. If droughts or diseases did not wipe out his stock he had a good chance of becoming a rich man.

During the 1830’s, a number of sheep farmers migrated to southern New South Wales from Tasmania and the area around Sydney. They founded Melbourne and occupied the rich grazing lands south of the Murray River. They did so well that they asked Great Britain to make them a separate colony. The request was granted in 1851. That year, the part of New South Wales south of the Murray River became the new colony of Victoria.

Gold fever

A clergyman who had been out preaching to the people on the sheep runs (овцеводческая ферма) once showed the governor of New South Wales some gold he had found. “Put it away”, said the governor, “or we shall all have our throats cut.” This was about 1840. New South Wales was still a penal colony. The governors wanted to keep order, particularly amongst the convicts. They imagined crime and chaos if there was a gold rush. So whenever reports of gold came in - and there were plenty of them - the governors hushed them up.

It took the cessation (прекращение) of transportation in 1840, and the Californian gold rush of 1848, to change official attitudes towards gold. By the end of the 1840s the government had decided that a gold rush was worth the risk. Any problems would be outweighed by the wealth gold would bring to Britain and her colonies. A reward was offered for the discovery of gold in payable (промышленный) quantities.

Edmund Hargraves had just come back from the goldfields of California. There he had learnt where to look for gold and how to mine it in various ways. Near Bathurst Hargraves he panned a few specks of gold from a creek and took the sample back to Sydney to show the governor. It was hardly sufficient to be considered “payable”, but Hargraves convinced enough people to start a rush, and collected the 10,000 pounds reward.

Hargraves discovering gold in Australia

For a few short years at the beginning of the 1850s hundreds of thousands of people flocked to south-eastern Australia. The ships that brought them often swung empty at their moorings (причал) as crews and passengers alike swarmed (лезть, карабкаться) inland towards rough-and-ready (сделанный на скорую руку) encampments in the bush. The lure was gold!

People seemed to lose their senses. Thousands dropped whatever they were doing and trudged off to the diggings to get rich. In the towns, men abandoned their jobs and businesses - and often wives and children. Sailors deserted their ships. On the sheep runs, shepherds and stockmen (ковбой) deserted their masters.

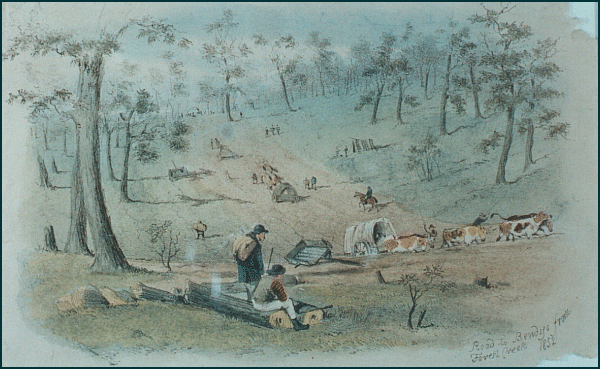

Road to Bendigo

A few months after the New South Wales rush began, gold was discovered in Victoria.

Appalled, the governor of Victoria wrote off to London about what had happened in the new colony. “Within the last three weeks the towns of Melbourne and Geelong . . . have been in appearance almost emptied of their male inhabitants . . . Cottages are deserted, houses to let, business is at a standstill, and even schools are closed.”

By early 1852 it seemed as though central Victoria was one vast, immensely rich goldfield. It also appeared that almost the entire population of the colony was heading for the diggings. Inland towns, and even Melbourne itself, were almost deserted. The government struggled to cope as most of its employees left their posts; eighty per cent of the police force resigned to go gold digging!

Gold pan used with water to separate gold from other particles

Even before the first gold discoveries in New South Wales, the world was already gripped by gold fever. The discovery of gold in California in January 1848 had triggered off the first great gold rush. The American discoveries excited considerable interest in Britain, but although many people were tempted, most prospective diggers held back (удерживаться). The Californian diggings were widely portrayed as dangerous hellholes, where life was the only thing that was cheap, and where lynch law alone reigned.

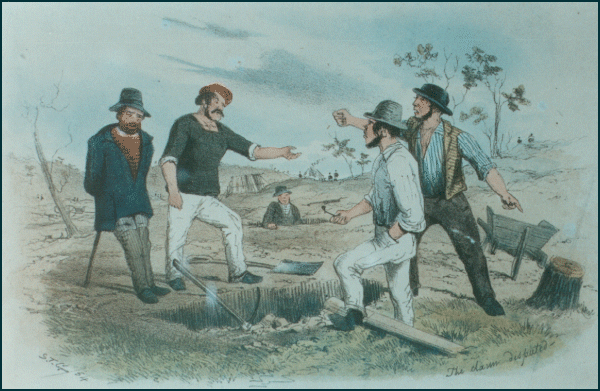

The claim disputed

The discovery of gold in the Australian colonies was a different matter. Here, few of the deterrents (сдерживающее средство) to Californian migration applied. British law was well established and early reports described the diggings as peaceful and orderly.

The first discoveries made in other states were: Western Australia in the early 1850s; Queensland in 1853; the Northern Territory in 1865; and Tasmania in 1877. Only South Australia failed to produce gold deposits of any significance.

People came to the colonies from all over the world. They came from Britain, America. Germany, Poland, Italy and China. There were rich and poor. There were many among them who had never done a day’s hard work in their lives. The aim was to get to a new field as quickly as possible, and stake a claim. The new diggers bought food, blankets, tents, guns, pots and pans and picks and shovels and began the long walk to the fields.

Many were optimistic about the discovery of gold. This was a chance for the working man to become wealthy through his toil. The well-known balladeer Charles Thatcher wrote:

On the diggings we’re all on a level you know;

The poor man out here ain’t oppressed by the rich,

But dressed in blue shirts you can’t tell which is which.

And this is the country, with rich golden soil,

To reward any poor man’s industrious toil;

There’s no masters here to oppress a poor devil,

But out in Australia we’re all on a level.

But others were worried. Men were leaving their homes and jobs for the goldfields. Homelessness became common because of the rapid increase in immigration, and prices for commodities were rising sharply. The fact that strength, not birthright, could become the most important factor in attaining wealth threatened the status quo. There was much anxiety that the obsession with wealth would lead to a crisis of morals. Catherine Helen Spence saw the rush for gold as a challenge to civilization:

This convulsion has unfixed everything. Religion is neglected, education despised, the libraries are almost deserted; nobody is doing anything great or generous, but everybody is engrossed by the simple object of making money in a very short time.

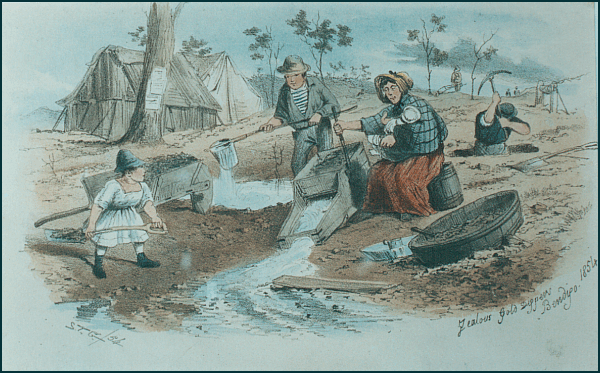

Zealous gold diggers

In summer the new roads were dustbowls. In winter horses and bullocks and people sank deep into the mud and the bush rang with the cracking of whips and the shouts and curses of men. The skeletons of animals lay on the roads whitening in the sun. Gold was like a lottery - the chance for a poor man to become rich. With luck anyone could do it. Or so it seemed.

Diggers’ hut

The gold rushes and the wealth they generated changed the course of Australian history. They ushered in a long period of prosperity and underpinned (способствовали) the development of a modern industrial base in the eastern colonies. The gold seekers brought to Australia a range of new skills and professions. Their sheer numbers created markets of a size few in Australia had dreamed of before gold. Moreover, these immigrants were often young, educated and energetic. With these qualities they transformed the political and cultural landscape of Australia, just as the wealth they dug from the earth transformed the economy.

Immigrants almost quadrupled the country’s population in the 20 years between 1851 and 1871, from 437 000 to 1.7 million. In 1851–1861, Australia exported more than 124 million pounds worth of gold alone.

People and organizations that had been trying to encourage emigration from Britain to Australia for some years saw the excitement created by gold as a heaven-sent opportunity to achieve their aims. Throughout 1851 and 1852 Charles Dickens, for example, published in his periodical Household Words a constant stream of useful information about the goldfields and the favorable prospects for active young Britons in Australia.

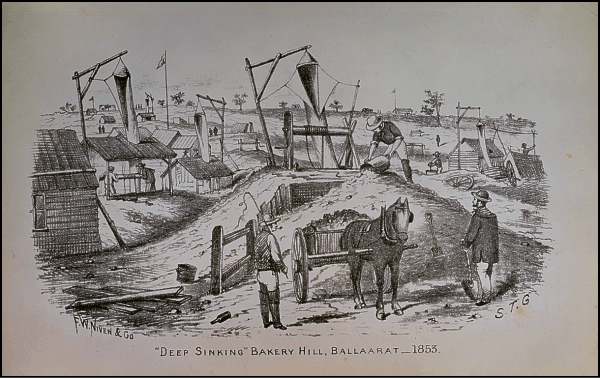

Cradling Cradle, used beside a creek or river, to separate water, rocks and gold, 1850s

It is estimated that 7098 tonnes of gold were mined in Australia between 1851 and 1970. In 1903 Australia was the world’s largest producer of gold.

Successful diggers on way from Bendigo

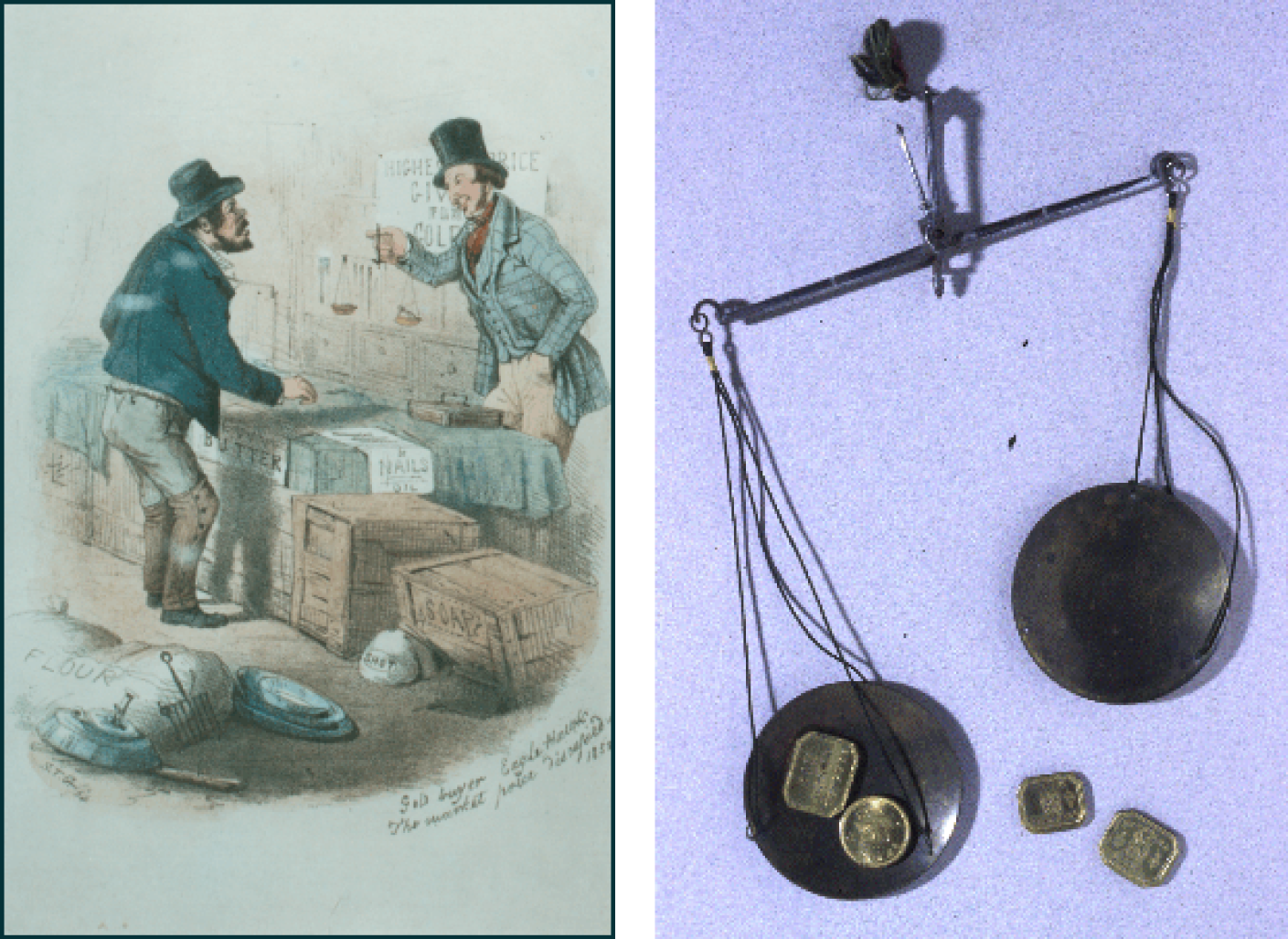

Gold buyer. The market price discussed Gold scales and weights

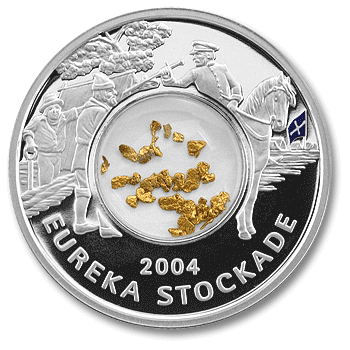

The Eureka stockade

During the first few years of the gold rush, digger had to pay a license fee of thirty shillings a month. This was more than many diggers would earn a month. The government hoped that a large fee would encourage people to stay in their jobs.

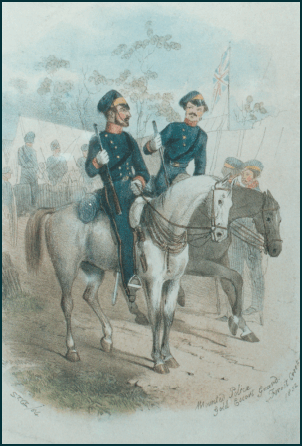

But people went to the fields just the same. Thousands more arrived every month from overseas. Those diggers who found a lot of gold did not mind the fee too much. But others objected to the monthly visits of soldiers and mounted police who collected the money.

Mounted Police

The miners came to hate the license hunters who were known as ‘Traps’. Word that they were coming was passed through the fields. When miners without licenses heard the cry ‘Trap!’ they hid themselves. But it was not easy to escape the license hunts. In Victoria in 1854 the governor had more than one thousand troops visiting the fields twice a week.

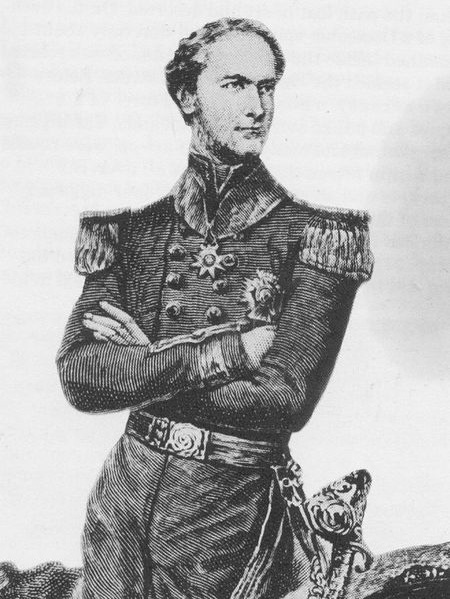

The Governor of Victoria, Sir Charles Hotham, contributed to the rising anger of the miners by levying heavy fees against them and by conducting military sweeps to catch those who had not paid the fees.

There were ten thousand men digging at Ballarat in 1854. Gold was becoming harder to find. Many of the diggers were desperately poor. There were men at Ballarat who said that they had come to Australia because they thought they would find more freedom here than in their own countries. Instead, they said, the colony was run by tyrants. Why should they pay a license fee when they had no say in the government? Some of the miners spoke of having a revolution like America had had.

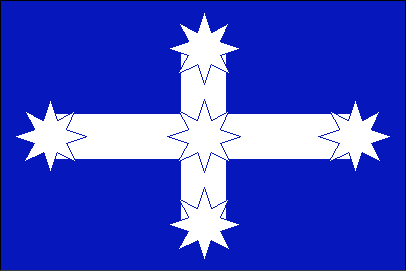

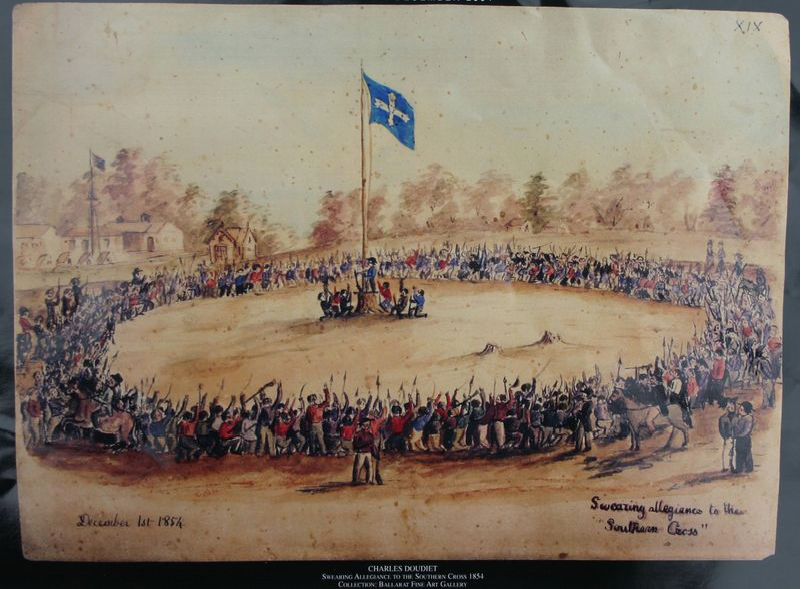

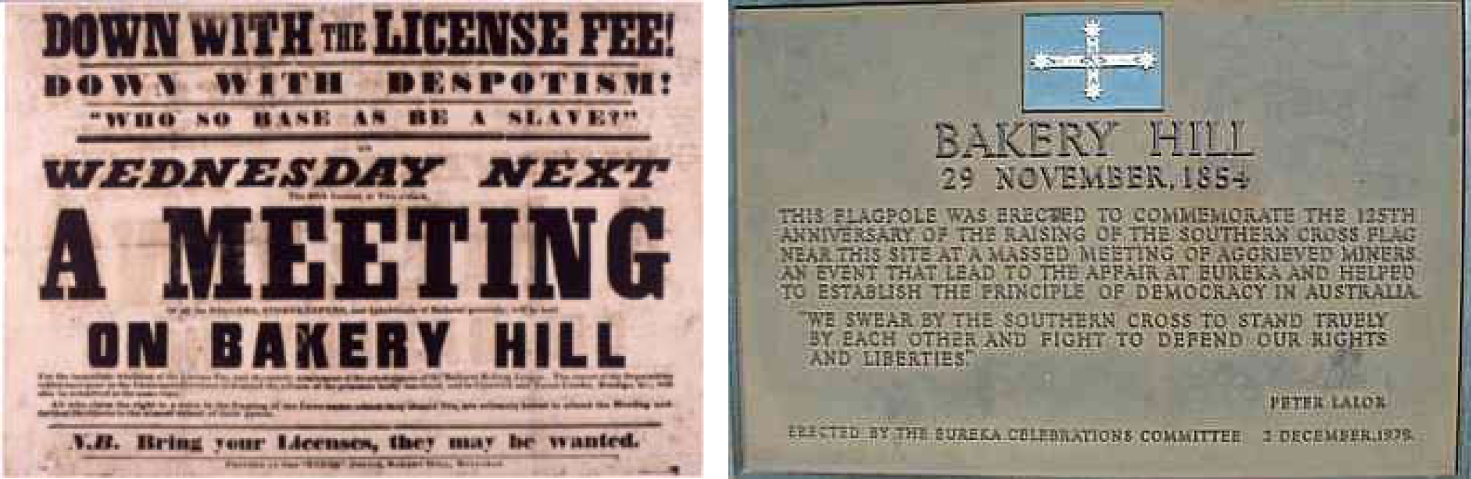

Meetings of thousands of diggers were organized. There were people from Ireland, England, Germany, Italy and America. The diggers declared that they wanted the license fee abolished and the right to vote at elections. They wanted democracy. At a meeting on Bakery Hill near Ballarat in 1854, ten thousand miners met under a new flag.

The men who raised it believed that it should be Australia’s flag. “There is no flag in Europe, or in the civilized world half so beautiful,” one said.

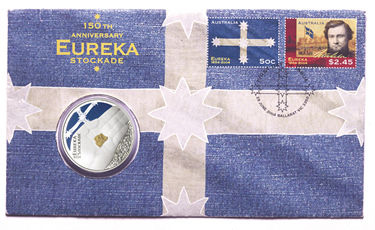

The Eureka Flag. This famous but unofficial Australian flag is believed to have been designed by a Canadian gold miner, “Lieutenant” Ross.

The torn remains of the Eureka Flag are kept at the Ballarat Fine Art Museum.

Swearing Allegiance to the Southern Cross on December 1, 1854

Under the flag the men burnt their licenses to show the governor that from now on they would defy (бросать вызов) the law. But the Governor was determined to defeat the miners. On the morning after the licenses were burnt, mounted soldiers charged a gathering of diggers injuring several.

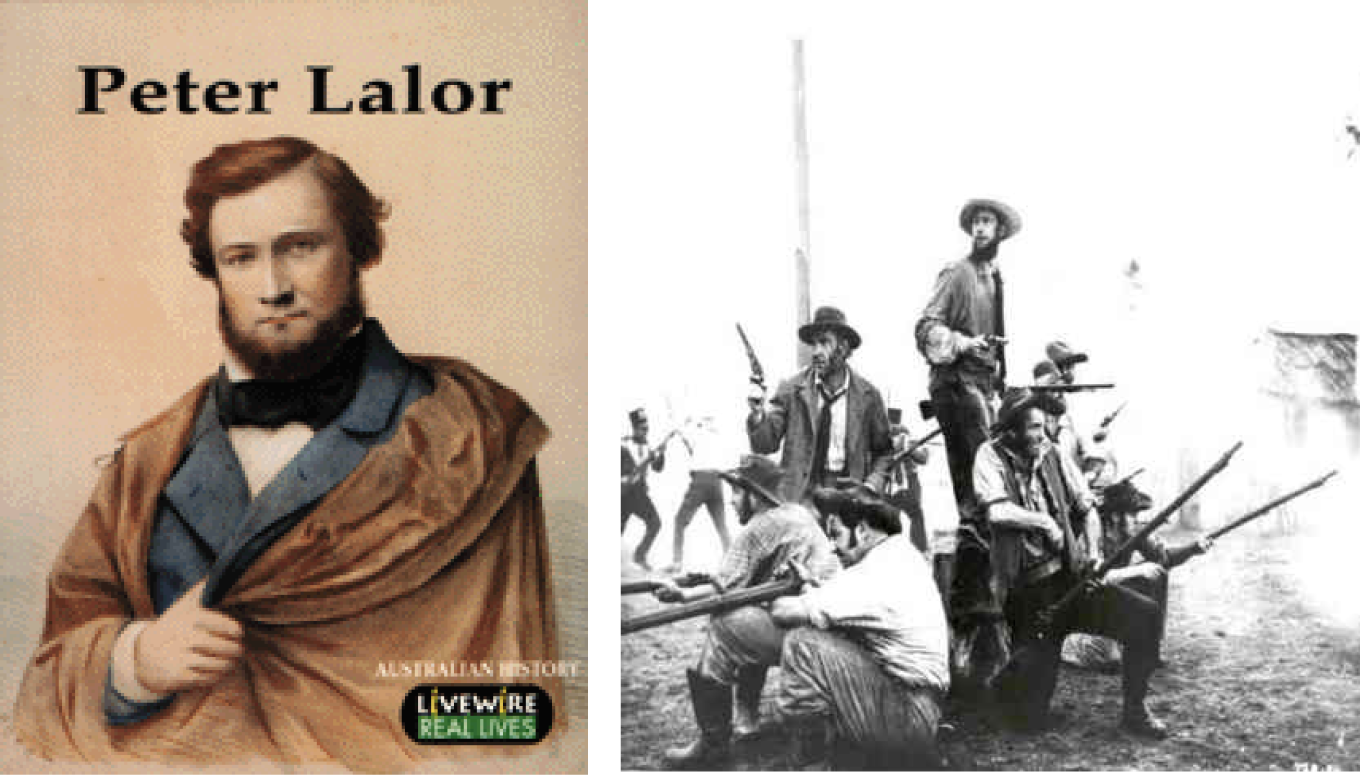

That afternoon the diggers met again on Bakery Hill. Peter Lalor, an Irishman, wrote later: “I looked around me; I saw brave and honest men, who had come thousands of miles to labor for independence. The grievances under which we had long suffered, and the brutal attack of that day, flashed across my mind; and with the burning feelings of an injured man, I mounted the stump and proclaimed “Liberty”.

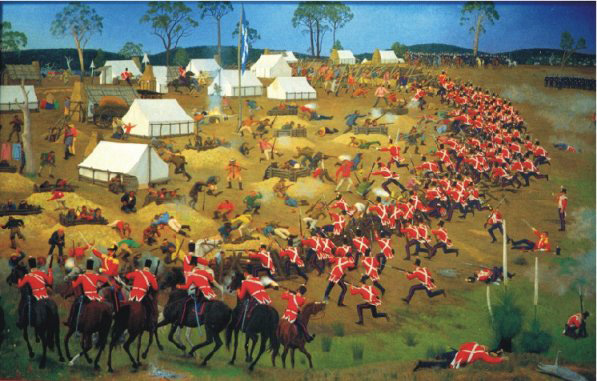

With Lalor as their leader the men armed themselves with guns and pikes. They marched to the Eureka field and built a stockade (укрепление, форт). They swore to defend the stockade against any attack. There were only about 150 men at the stockade at dawn on Sunday, 4 December 1854. A lot of them were asleep when about three hundred soldiers charged. Ten minutes later about thirty miners and six soldiers lay dead or dying. The soldiers rounded up the surviving diggers who had not fled and marched them off to jail. Peter Lalor was wounded in the battle but managed to escape. That night he hid in the house of a priest and his wounded arm was amputated.

300 soldiers are surrounding the gold miners at the Eureka stockade at dawn

The miners at Eureka had lost the battle but most people in Victoria were on their side. The newspapers condemned the soldiers’ brutality and said the governor should not have ordered the attack.

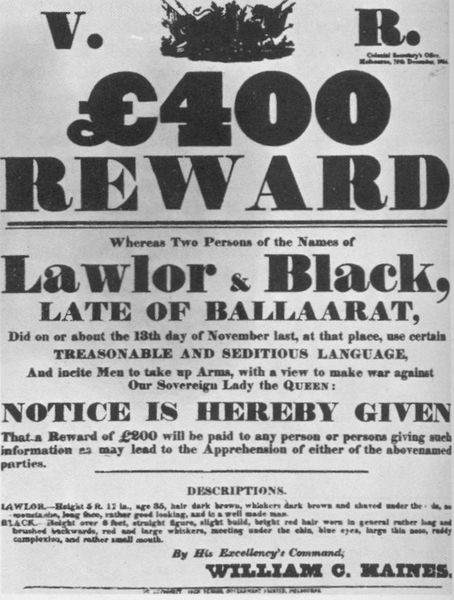

A reward of 400 pounds was issued for Peter Lalor

The miners who had been arrested and charged with high treason were found not guilty. Outside the courts crowds gathered and cheered when the verdicts were announced. A new government was elected in 1855. The license fee was abolished. In future miners would pay just one pound a year for a ‘miner’s right’ - the right to dig for gold and the right to vote.

... I think Eureka may be called the finest thing in Australasian history. It was a revolution – small in size, but great politically; it was a strike for liberty, a struggle for a principle, a stand against injustice and oppression. It was another instance of a victory won by a lost battle.

(Mark Twain, American authour)

The diggers were subjected to the most unheard of insults and cruelties in the collection of this tax, being in many instances chained to logs if they could not produce their licence.

(Peter Lalor, digger)

Lalor, who lost an arm in the Eureka Stockade rebellion that he led, later went on to become a Member of Parliament

But not in vain those diggers died. Their comrades may rejoice.

For o’er the voice of tyranny is heard the people’s voice;

It says: “Reform your rotten law, the diggers’ wrongs make right.

Or else with them, our brothers now, we’ll gather to the fight.”

(Henry Lawson (1867 - 1922), Australian poet and author)

Ballarat today

150th anniversary official commemoration, December 3, 2004

Foreign devils

There were about two thousand Chinese people in Australia when the gold rush started. They had been brought out by squatters to work on their runs as shepherds and laborers. Others worked as cooks and household servants.

Thousands more Chinese came when news of the gold discoveries reached them. A lot of Chinese who sailed for Australia never saw the goldfields. Conditions on the ships from the Chinese ports were as bad as any convict ship. Hundreds died on the voyage. White settlers in the colonies were amused by the Chinese migrants. They joked about the pigtails they wore. The Chinese all seemed to dress in the same blue jumpers and trousers, shoes made of silk with wooden soles, and wide brimmed straw hats.

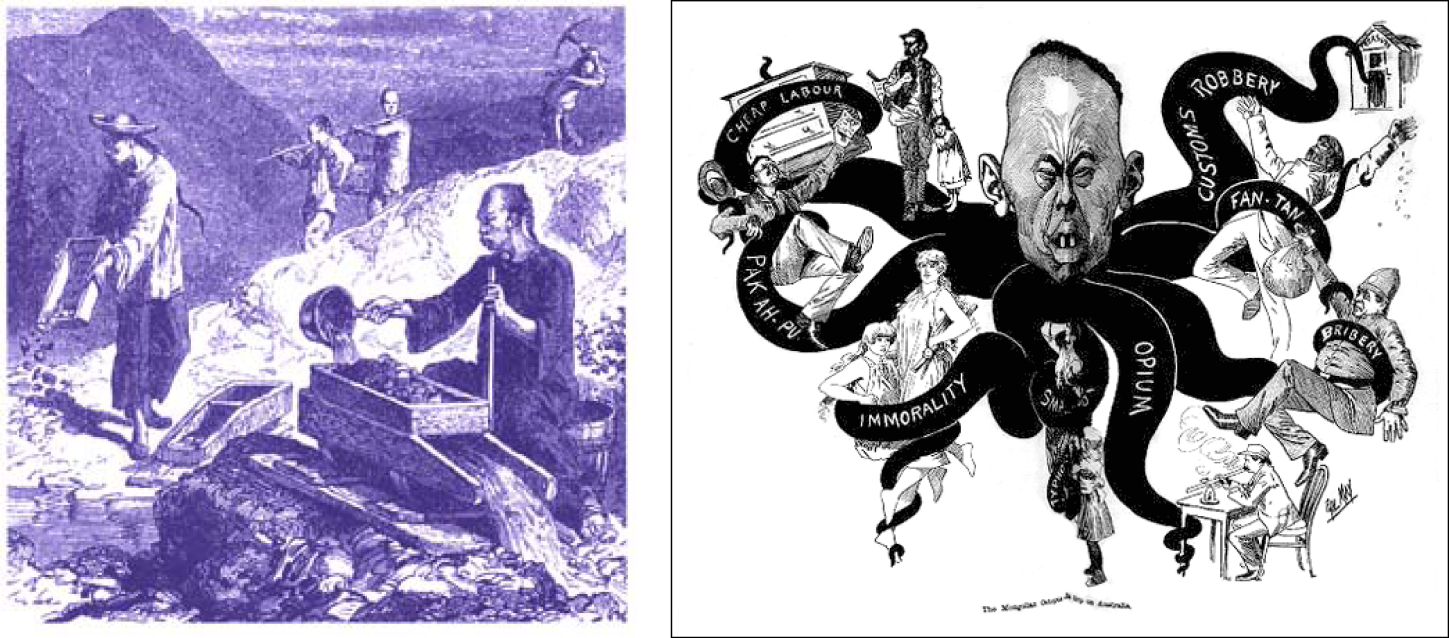

The Chinese worked very hard on the goldfields. A very large Chinese camp was established at Guildford in Victoria. At one time there were more than five thousand Chinese there, all of them working over an abandoned mine which the European miners had given up. At first the Europeans did not mind the Chinese coming. But as the gold ran out they started to resent them - particularly as they seemed to be able to find gold where Europeans could not. The Europeans began to say that the colonies of Australia should only be open to other Europeans.

The Chinese were described as a threat to British civilization in Australia. It was said that they were opium smokers. A lot of Chinese did smoke opium, but it caused much less havoc than the alcohol Europeans drank. They were portrayed as dirty and disease-ridden. Newspapers had pictures of Chinese men looking like hideous fiends (ужасные злодеи). Readers were told that they made a habit of stealing European women. In Victoria a special tax was put on the Chinese. They were made to pay a fee when they arrived in the hope that this would stop them coming.

In some places the Europeans attacked the Chinese and beat them viciously. The tents of the Chinese were pulled down and burnt. Some Chinese were killed. The worst attack was at Lambing Flat in New South Wales in 1861.

Hatred for the Chinese became a way of thinking in Australia. Eventually all the colonies passed laws to keep them out.

The Chinese Octopus – His Grip on Australia’ in “The Bulletin”, 21 August 1886

Ever since the arrival of large numbers of gold-seeking Chinese immigrants to Victoria in the 1850s, most of the press had portrayed Chinese people with derision and prejudice. This cartoon portrays opium smoking, disease, corruption and sexual immorality, alongside cheap labor, as Chinese vices.

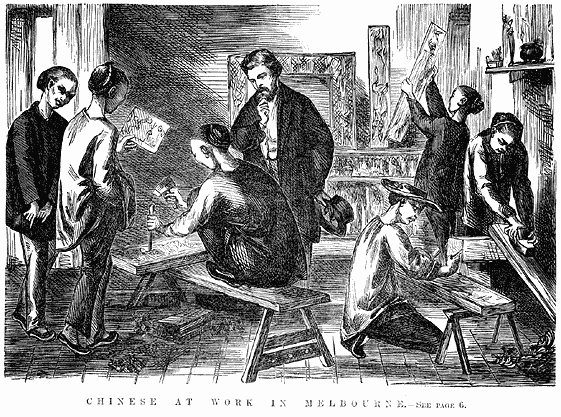

‘The Chinese at Work in Melbourne’ in “Australian News for Home Readers”, March 1867

Chinese workers in Melbourne were seen as a threat to the working conditions and jobs of others, because of their low rates of pay and their long working hours, particularly in the furniture industry. Furniture was often stamped ‘European Labor Only’ to encourage people to discriminate against furniture made by Chinese workers.

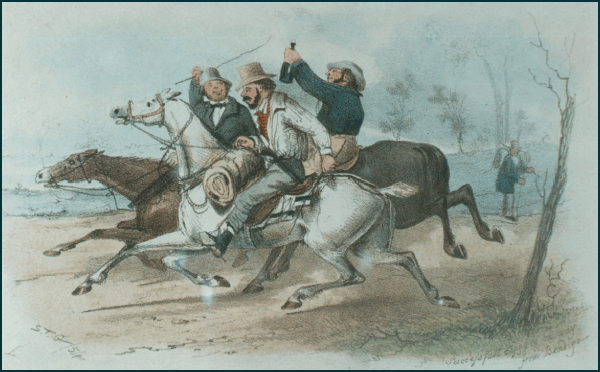

The bushrangers

The bushrangers of the ‘gold rush’ era were active around the goldfields areas. Some were ex-convicts, but many were just unfortunate victims of hard economic times who took to the roads as an easy way to exist.

Many were born in the bush and had an expert knowledge of horses and firearms, and the plains and mountain ranges they roamed in search of fortune and adventure. They had little regard for authority and no sympathy for weakness. The rush for gold following massive discoveries in Victoria in the 1850’s presented ideal circumstances for them to exploit their skills and delinquency.

Law and order in the colonies had been hampered by the mass exodus of law enforcement officers from jails and the police force to the goldfields. Thousands of head of livestock (скот) went unattended as shepherds and farm workers walked off the land to seek their fortunes. A bush-ranger found this easy pickings (воровство), supplying stolen horses, cattle and sheep to the earnest diggers, while the depleted law enforcement authorities had little chance and few resources to restrain them.

They next turned to the easier business of stealing gold as it was transported from the diggings to the major cities of Sydney and Melbourne. It became dangerous to travel the roads around the diggings and even well-armed parties were under threat if it was know they were carrying bullion (слиток золота).

While few of the bushrangers ever achieved the riches to enable them to escape their circumstances, many gained notoriety, and some even achieved the status of folk heroes. Sections of the poorer classes in Australia identified with the bushrangers’s contempt for authority.

The names of Ben Hall, Ned Kelly, Frank Gardiner, ‘Mad Dan’ Morgan, Johnny Dunn, Johnny Vane, Martin Cash, and the Gilbert brothers are names linked with the rich, colourful and dangerous history of the gold rush.

Originally, the term bushranger referred to any person who worked in or made a living from the bush. It included hunters, wood splitters, etc. Eventually it came to mean any criminal who lived in the bush and made his living out of plundering travelers and bush dwellings.

Today, the word bushranger has adopted a more romantic meaning, referring to skill in bushcraft, knowledge of the bush, horsemanship, daring and gallantry and the concept of roaming the bush, wild and free, in defiance of authority‚ rather than the emphasis of banditry, robbery, murder, plundering, horse and cattle duffing (воровать скот, менять клеймо) and other serious crime which more properly defines the real activities of the bushranger.

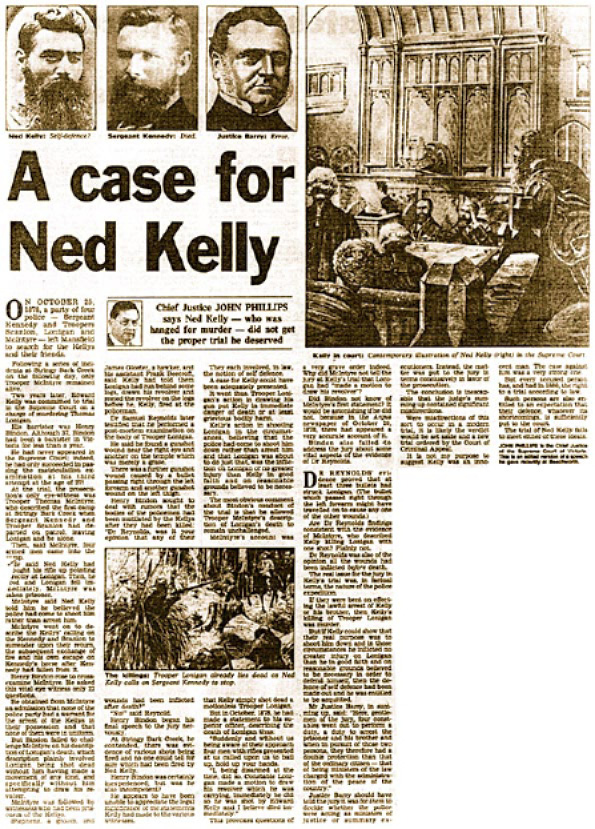

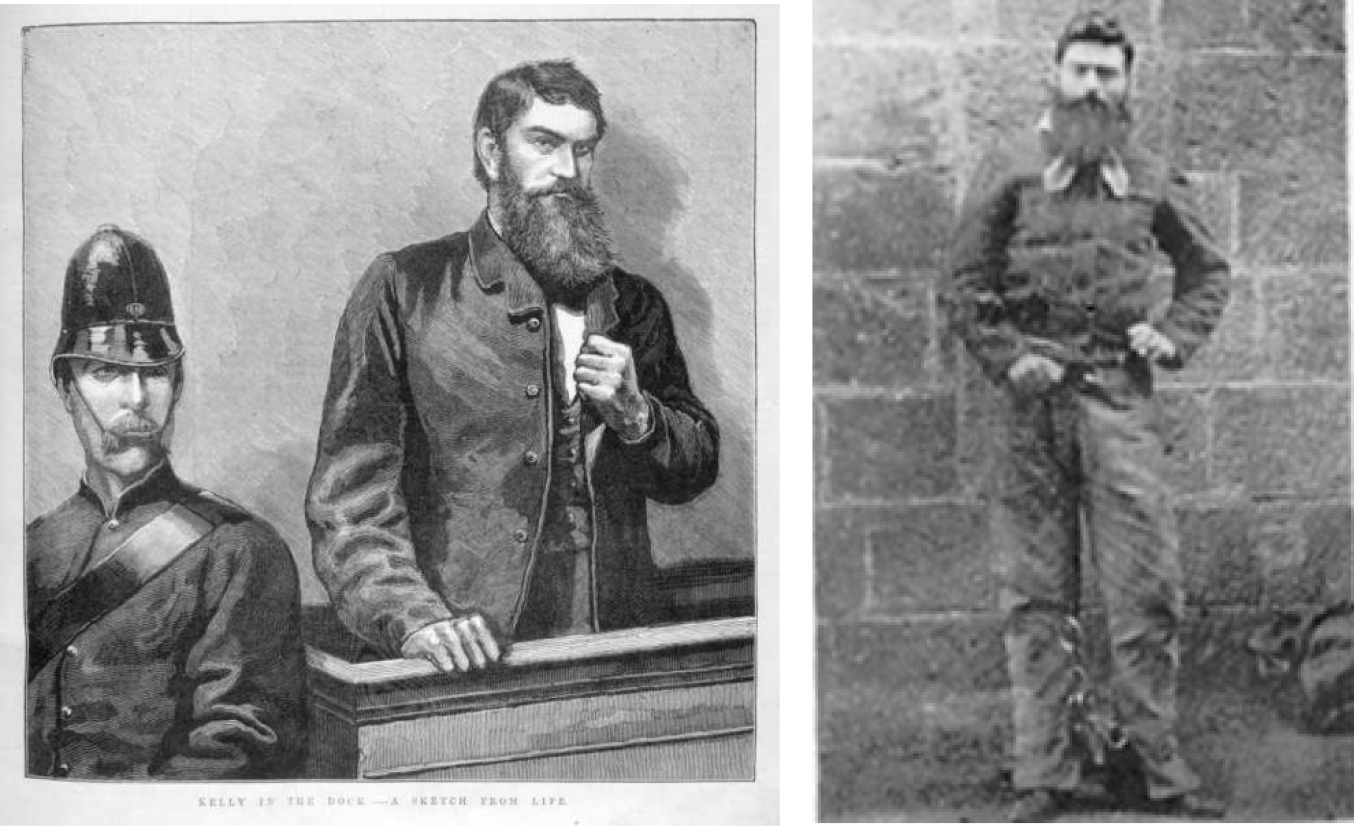

Ned Kelly

Ned Kelly is the most famous of all Australian bushrangers. He was born in the Glenrowan area in 1855 and at age 15 had his first altercation (ссора) with the police. He was charged with helping bushranger Harry Power, during robberies.

Shortly after, he was sentenced to 6 months hard labor for assault and indecent behavior.

After his release, he got a job working in a saw mill and stayed out of trouble for a time. He developed a reputation as a rider and boxer during this time, and seemed to have learned his lesson well.

When the saw mill closed in 1876 he was accused of stealing a bull, and soon became a target of the police who took out their frustrations on his female relatives. Kelly’s resentment of this harassment grew and he developed a hatred for the police, which lasted through his short lifetime.

Over the next few years the police tried many times to gain evidence on Kelly to get him behind bars (за решетку) until, on the 20th of June, 1880, Kelly with a gang comprised of his brother and others, attacked Glenrowan, cutting the telegraph wires. In the ensuing gun battle with police Kelly was shot in the knee and captured. On 11 November 1880, at the age of twenty-five, he was hanged in the Melbourne jail. His last words were “Such is life”. Some 4,000 Melbourne people attended the hanging.

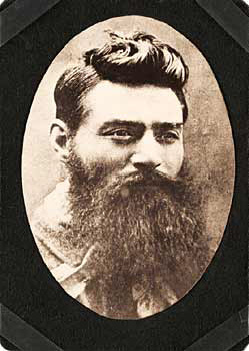

The suit of armor which Kelly designed to protect himself in running gun battles with police is now a part of Australian folklore. It comprised an iron helmet, something like an inverted bucket, with a slit for the eyes to see through.

Suit of armor (44 kilos) worn by Ned Kelly

Ned Kelly is an integral part of Australian folklore and expressions like “As bold as Ned Kelly” have become part of the language. A statue of Ned Kelly wearing his famous armor will be found in the town of Glenrowan. He is buried in the Old Melbourne Jail.

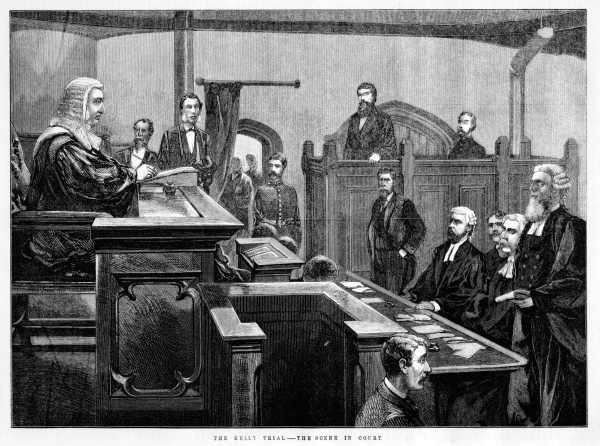

The trial of Ned Kelly

Ned Kelly the day before execution

The execution of Ned Kelly

Ned Kelly’s death mask

1 Damper (австралийский хлеб).