COLONISATION OF AUSTRALIA

There were several reasons why the British government decided to make a settlement in Australia.

By the eighteenth century the people who had once lived and worked on the land were being steadily driven from it. Food shortages, harsh penal laws, and the general displacement of people during the early stages in the Industrial Revolution in Britain added to its criminal population. In the rural areas of Britain many people turned to crime – either to survive or to protest at the way landowners treated them. They poached (заниматься браконьерством) animals from the estates and sometimes destroyed the crops and machinery of the owners. In the cities the poor lived in squalor, without work or money, decent food, clothing or housing. Britain in those days included all of Ireland as well as Scotland and Wales. The Irish resented the English control over their land. They tried to drive them out by destroying the property of English landowners.

The government responded to the increase in crime by extending the criminal code to make even the most minor transgression (правонарушение) a capital offence. In 1778 there were about two hundred ‘crimes’ which carried the death sentence.

In 1787, when the first fleet of convicts and soldiers left Portsmouth Harbour for Botany Bay on the other side of the world, the jails of Britain were full.

The ramshackle (ветхий) system of local prisons could not accommodate the swollen numbers of convicts. British jails were foul-smelling, dank (сырой) and dark places which contained people who resented the treatment they received. About half the jails of England were privately owned and run. Chesterfield jail belonged to the Duke of Portland, the Bishop of Ely owned a prison, the Bishop of Durham had the Durham County Jail and Halifax jail belonged to the Duke of Leeds. The jailers were not State employees but small business operators, malignant landlords who made profits from extorting money from prisoners.

Since the days of Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603; Queen 1558-1603), the British had been getting rid of troublemakers by banishing (изгонять, высылать) them abroad or putting them to work rowing the galley (галера) ships. Leading social reformers of the day assumed that the best way to eliminate crime was to remove these criminals from society.

Queen Elizabeth I

“Transportation” as a punishment had been established in 1717, when most felons sentenced to transportation were sent to the American colonies. Planters in America needed labor force to do the work. They used slaves brought from Africa and convicts. Between 1718 and 1770 about 30,000 convicts were transported to the British colonies in America.

In 1776 the Americans fought a war with the British and won their freedom to govern themselves. Britain no longer had a place to send convicts. Until a place could be found to send them they were confined in the hulks (корпус) of old ships on the River Thames. Some convicts were shipped out to places like central Africa, but the climate there was so terrible most of them died.

In 1786 the government decided to send convicts to the east coast of Australia, to Botany Bay – the place Captain Cook had visited in 1770. This seems to be an expensive solution to the problem. Running a jail nearly twenty thousand kilometers away would cost the government a lot of money. The British, however, saw other advantages in starting a settlement at Botany Bay. They planned to grow flax (лен) to make sailcloth (парусина) for ships, and to harvest the tall pine trees on nearby Norfolk Island to make masts.

Norfolk Island

The British also wanted a new base for their trade with China. A settlement at Botany Bay would also be useful in case of war with the Dutch or the French who had interests in the region.

For all of these reasons the British government in 1787 sent 759 convicts to Botany Bay. As capital punishment became less popular in England, more and more prisoners faced sentences of transportation, in most cases for seven years, but sometimes for life. Over the next seventy years 160,000 convicts would be sent on that long voyage to an unknown land. Once in Australia, the convicts were assigned to either the government or to traders as labor.

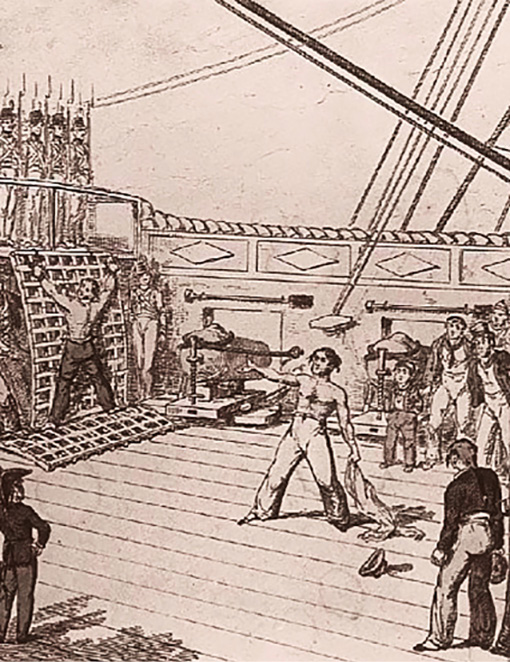

The ships that transported convicts to Australia were foul smelling, dark and dank places. Prisoners were often shackled (приковывать) to bulkheads (переборка; шпангоут) and each other in overcrowded barbaric conditions. The sea passage which lasted for many months were unpleasant, unhealthy and dangerous. On board the ships there was real misery, stench, heat, cold, constipation, dysentery, vomit, boils (нарыв, чирей), scurvy (цинга), dampness (сырость) and mouth rot. There was also hunger, thirst, anxiety and frustration.

The First Fleet

The First Fleet, consisting of two warships, six transports and three storeships, carried seeds and seedlings (рассада, саженец), ploughs and harnesses, horses, cattle, sheep, hogs, goats and poultry, and food for two years. Besides, the fleet carried

747 000 nails,

10 000 bricks,

8 000 fish hooks,

5448 squares of glass,

2780 woolen jackets,

327 pairs of women’s stockings,

60 padlocks,

26 marquees (большая палатка) for married officers,

7 dozen razors,

6 harpoons,

3 candle snuffers (щипцы для снятия нагара со свечи),

Governor Phillip’s dogs,

Reverend Johnson’s cats and

a piano.

Under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip (1738-1814) of the Royal Navy, eleven ships carrying over 1400 people sailed from Portsmouth on 13 May 1787. Bound for Botany Bay in the colony of New South Wales, the First Fleet covered over 15 000 miles in eight months.

Captain Arthur Phillip

Leaving Portsmouth

Six transports carried the 759 convicts while three storeships (транспорт снабжения) provided supplies and two men-of-war (военный корабль) protected the fleet. Some of the officials and even a few of the convicts brought their wives with them. There were thirty-seven children.

The convicts were now selected on the basis of useful skills as Phillip wanted; the authorities seized the opportunity to get rid of the useless, the sick, the aged, the troublemakers and the discontented (недовольный).

The voyage of the First Fleet was arduous (трудный) and long. On board the convicts were crammed into spaces between the decks just 137 cm high. They slept in double bunks (койка) 90 cm wide – just 45 cm for each convict. Lying down was almost as uncomfortable as standing up. Few of them had been to sea before. Fewer still had the faintest idea where Botany Bay was. Near the equator ships entered the doldrums (штиль). Often they lay for days without a breath of wind to move them. Between the decks the convicts lay stifling. ‘The sufferings of the imprisoned wretches in the steaming and crowded hold were piteous to see,’ said a man who travelled on a convict ship in 1797.

Flogging

Phillip knew that he had a difficult task taking the dregs (отбросы) or English prisons to New Holland, for he had been a mercenary In the Portuguese government employ transporting convicts to Brazil. He gave orders that the convicts were to be allowed on deck for fresh air and exercise. He demanded that all convicts should be clean and suitably clothed. No soap was issued for the convicts, so half the soap allotted to the two hundred and fifty sailors was given to the prisoners. Preparations for the trip were so bad that he was sure halt the prisoners would die. Yet after a fifteen-thousand-mile trip lasting over eight months there were only thirty-two deaths.

The highlights of their progress were as follows:

13 May 1787 – Depart (отплытие из) Portsmouth, England

3 June 1787 – Arrive (прибытие) Teneriffe, Canary Islands

10 June 1787 – Depart Teneriffe, Canary Islands

5 July 1787 – Cross Equator

6 August 1787 – Arrive Rio De Janeiro, Brazil

4 September 1787 – Depart Rio De Janeiro, Brazil

13 October 1787 – Arrive Cape Town, South Africa

12 November 1787 – Depart Cape Town, South Africa

1 January 1788 – Adventure Bay, Van Dieman’s Land

18 January 1788 – Arrive Botany Bay, New South Wales

26 January 1788 – Arrive Port Jackson, New South Wales

11 ships under command of Arthur Phillip on their way to Botany Bay

Since in Australia there was no one to buy convict labour, they were expected to become a self-sufficient community of peasant proprietors. Of the 736 who were selected, the men outnumbered the women by three to one. Because there was no government, it would be a military colony.

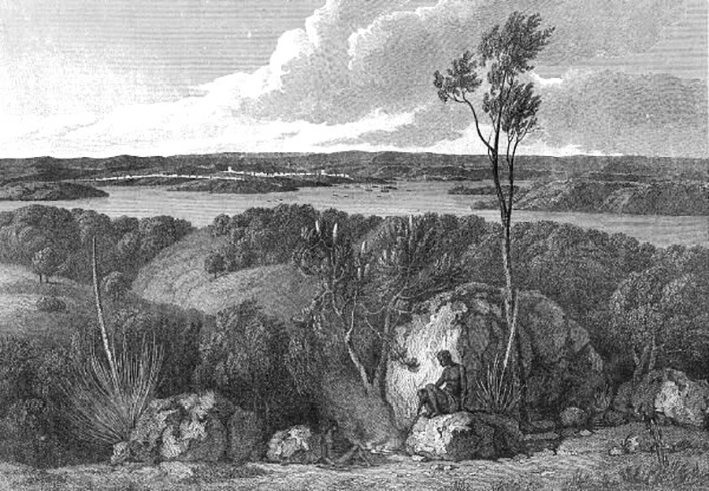

Phillip arrived at Botany Bay on January 18, 1788. Finding the bay a poor choice, he moved north to Port Jackson, which he discovered to be one of the world’s best natural harbors. Here he began the first permanent settlement on January 26, now known as Australia Day.

View of Port Jackson, 1788

January 26, 1788,Arising of the British flag

Sydney was established on this site

Port Jackson today

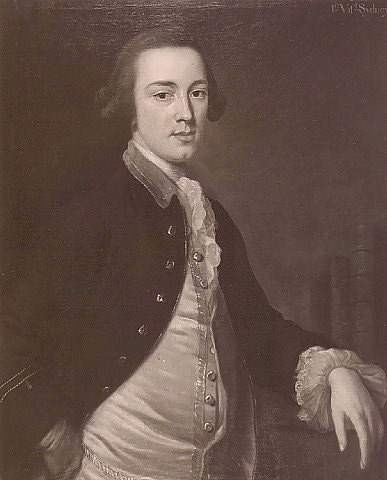

The settlement was named Sydney for Britain’s home secretary, Lord Sydney, who was responsible for the colony.

Lord Sydney Britain’s home secretary

Captain Arthur Phillip

The male convicts came ashore first. On 3 February a sermon was preached to them by the Reverend Johnson. No women were present at either the first raising of the flag or the sermon. They were not brought ashore until 6 February, eleven days after the first fleet’s arrival.

A depiction of the founding of Britain’s first prison colony in Australia

Before leaving England, Phillip had asked for an advance party to be sent out to obtain information. This request had been brushed aside, as had also his plea for better provisions, since the government was anxious to get the convicts out of the way as quickly as possible. Hence no one really knew what Australia was like. There had been no surveys to find out about the climate, rainfall, soil, vegetation and wild life. In the party there was not a single botanist or farmer, except Phillip himself, to advise the settlers how to grow crops and produce their own food. They had no draught horses (рабочая лошадь), no manure (навоз) to enrich the sandy earth, and most of the seeds had been spoilt on the voyage out. The hand tools supplied by government contractors were the cheapest and poorest obtainable.

Phillip’s domain (владения) covered half of Australia (from the eastern oceanic waters to as far west as the 135th meridian), but his human resources were limited. In particular, he lacked the horticulturalists (only one of the convicts was a farmer), skilled carpenters, and engineers needed to develop a self-supporting colony. Most convicts were urban residents of a working class background with few of the skills and none of the pioneering attitudes essential in a new colony. Research into their backgrounds reveals that overall the convicts were illiterate, prone (склонный) to drunkenness and promiscuity, idle and unwilling to work. The bulk of these people were habitual offenders and incorrigible (неисправимый). A minority of the prisoners were from the upper class and were serving sentences for crimes such as forgery; these convicts were often able to use their training in business and in government offices. In general, however, because they were unskilled and unaccustomed to the rigors of colonial or prison life, the convicts were an exceptionally difficult population with which to build a new society. No wonder Phillip wrote home in exasperation: “If fifty farmers were sent out with their families they would do more in a year . . . than a thousand convicts.”

The marines (солдаты морской пехоты) were not keen to help build a settlement. They felt that their job was only to defend it.

Three major problems confronted the early governors:

– providing a sufficient supply of foodstuffs;

– developing an internal economic system;

– producing exports to pay for the colony’s imports from Britain.

From the start the Governor was anxious about the stores. He had provisions that were supposed to be sufficient to last for two years, but when they were opened they were found to be of very poor quality and some were mouldy (заплесневелый) and almost useless.

Within a year the colonists were nearly starving. Food was in such short supply Phillip warned the convicts and marines that anyone who stole the “most trifling” article would be hanged. The first execution in Australia was a 17 year old youth named John Barrett, for stealing food, on the 6th of March, 1788. A dozen or more were hanged in the first year, from a tree between the male and female quarters. In these first years stealing a fowl or a piece of salt pork was enough to have a man or woman “launched into the other world”.

At Rio de Janeiro the first fleet took on “all such seeds and plants . . . as were thought likely to flourish on the coast of New South Wales, particularly coffee, indigo, cotton, and the cochineal fig”. At Cape Town they brought on board close to five hundred animals, including fat-tailed sheep, cattle, pigs and poultry (домашняя птица). The sight reminded one officer of Noah’s Ark. But the first vegetables and grain planted did poorly in the Sydney soil. Fresh meat was very scarce, for the colony’s entire livestock numbered only 2 bulls, 5 cows, 1 horse, 3 mares, 3 colts, 29 sheep, 19 goats, 74 pigs, 5 rabbits, 18 turkeys, 29 geese, 35 ducks and 210 fowls. After the long voyage the stock was in poor condition and the animals did not thrive on the coarse grass of the area. The cattle wandered off into the bush and were not found for years. All but ten of the sheep were killed by lightning shortly after landing. Even the rabbits, which were to become a pest (вредитель) seventy years later, did not increase. Rain, rats and weevils (долгоносик) destroyed much of the seeds.

Natural food sources were largely limited to fish and kangaroo. Although they had guns the British were at first not very expert at hunting the wild animals. Phillip tried to find out how the aborigines managed to live in this inhospitable land but, although he had prisoners taken, they told him little that a European could understand about their way of life.

Some colonists died, but others survived by eating grass, rats, crows and lizards; if someone shot a wild dog, he cooked its flesh and made soup from the bones. The chief surgeon wrote, “not one ounce of fresh animal food since first in the country; a country and a place so forbidding and so hateful as only to merit curses.”

Clothing was chronically short and even eleven years later men were still working naked in the fields.

Phillip established farms on the more fertile banks of the Hawkesbury River, a few miles northwest of Sydney, but this land was often flooded or still used by the Aborigines. Needed food supplies came mainly from Norfolk Island, nearly 1600 km away, which Phillip had occupied in February 1788.

But Phillip kept his faith in the venture, he was sure it would succeed if the British government would do more to encourage free people to come out from Britain. Phillip believed free emigrants would come if they were offered grants of land. The colony would prosper because they would work hard while the convicts could be put to work for them. But, to people in England, America was a more attractive place. It was easier to get there and easier to return home. Only 13 free migrants came to New South Wales in the first five years.

By the end of 1789 the people at Port Jackson were beginning to think they had been abandoned. No supplies had arrived and one of the colony’s two supply ships had sunk near Norlofk Island. They were saved by the arrival of the second fleet in June 1790. But the ships brought new problems. It had been an awful voyage. Of just over 1000 convicts who had left England, 267 had died of scurvy, dysentery and fever. On one ship, Neptune, one in every three convicts had died. More than 120 convicts from the second fleet died after landing.

It was a similar story with the third fleet which arrived the following year. But somehow the settlement began to establish itself. Some of the marines decided to stay. They were given grants of land and assistance in farming it. Some convicts were also granted small plots when they had served their sentences. They were called emancipists – people who had been set free.

In October 1792, three and a half years after the first fleet had arrived, Phillip proudly reported that nearly 5000 bushels of maize (кукуруза) had been harvested. There were 1700 acres under cultivation. Whalers (китобойное судно) and sealers (охотник на тюленей) had begun operating from the port. It was still a tiny settlement on the fringe of the continent, but it was beginning to look like it could last. Phillip returned to England in December 1792 convinced that New South Wales would one day be ‘the most valuable acquisition that Great Britain ever made’.

Port Arthur, Tasmania, was Australia’s largest penal colony.

Religious tolerance in early Australia

When the first fleet of English settlers, predominantly convicts, landed in New South Wales in 1788, their numbers included one chaplain representing the Anglican Church. Although there is evidence that he was not received too well by the new colonists (the first church he built is said to have been burned down by the congregation), the Church of England was intended to be the established religion, and no others were to be tolerated. Strict intolerance became more and more difficult for the government to encourage, however, as Irish Catholic convicts began to arrive soon after. Catholics were still restricted at the time in England, but the new English statesmen of Australia began to see a necessity, in the interest of public order, for an increase in tolerance. A belief that any and all religion discourages swearing, drunkenness, gambling and other unruly behavior while it promotes hard work and peaceful values became a necessary factor in the change in state policy. It was this change that would lead to government aid for the building of Catholic churches in the colonies, and it was this aid that soon would lead to similar demands from other denominations.

Tolerance of the native Aborigines did not seem to be a consideration of either the settlers or their government. Cultural differences between the colonizers and the Aborigines seemed insurmountable, and religion was most likely a great factor in the misunderstandings and abuses. Historian C.M.H. Clark writes that “the white man came bearing his civilization as his offering, expecting the aborigine to perceive the great benefits he would receive at its hand, including that benefit of being received into the Church of England, which was believed to contain all that was necessary to salvation.” The failure of this plan is described by Clark as having “puzzled” the new Australians, who “remained strangers to [the Aborigines’] religious rites and opinions.”