Movement toward Federation

In 1866 Victoria, followed by South Australia and Tasmania, adopted a policy of high tariffs on imported goods in order to protect its own small industries and markets. New South Wales (and Queensland to a lesser extent) continued to stay with a free-trade policy.

Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, the arguments over free trade versus protection divided the press, the political parties, and the colonies. This, together with the continuing jealousies among them, hindered any significant attempts at cooperation and possible union among the six colonies until the 1890s.

The rapid increase of Australia’s population from 1830 to 1860 contributed to the growth of the six capital cities. With the decline of gold mining in Victoria and New South Wales in the 1860s, even the prospectors drifted to the cities. By the end of the century, Sydney and Melbourne were among the world’s largest cities.

Each capital served as the major port for its respective colony. Perceiving others as rivals, each city—and colony—tended to emphasize its own identity. Contacts between individual colonies were secondary to their ties with Britain, and rivalries among them were common; thus, Victoria and New South Wales each used a different gauge (ширина колеи) for their railroads.

As the number of free settlers in Australia grew, so did the colonists’ demands for self-government. By 1856, Britain had granted self-government to all the colonies except Western Australia. Each had its own elected legislature and government ministers, who controlled the colony’s internal affairs. Britain continued to manage the foreign affairs and defense of the colonies. Meanwhile, squatters had settled the part of New South Wales north and west of Brisbane. In 1859, Britain created the colony of Queensland out of this area, with Brisbane as its capital.

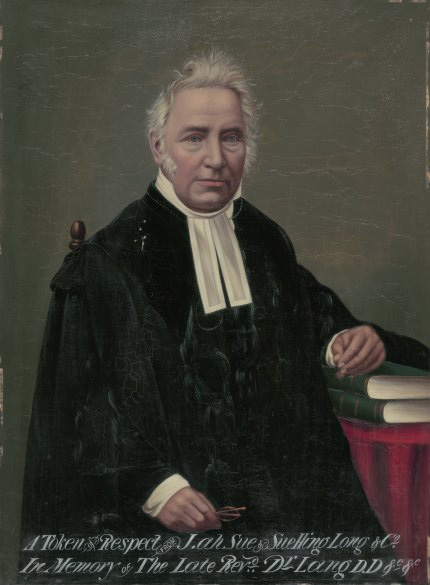

Federation of the Australian colonies came late. The idea of unification appeared as early as 1847 in proposals by Earl Grey, Britain’s colonial secretary. In the 1850s John Dunmore Lang, a Scottish Presbyterian cleric in New South Wales, formed the Australian League to campaign for a united Australia. Conferences among colonial governments in the 1860s also considered closer cooperation and unification. With the formation of the Dominion of Canada in 1867, British officials began to expect a similar effort among Australians.

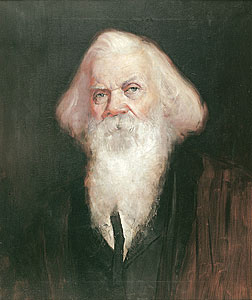

John Dunmore Lang

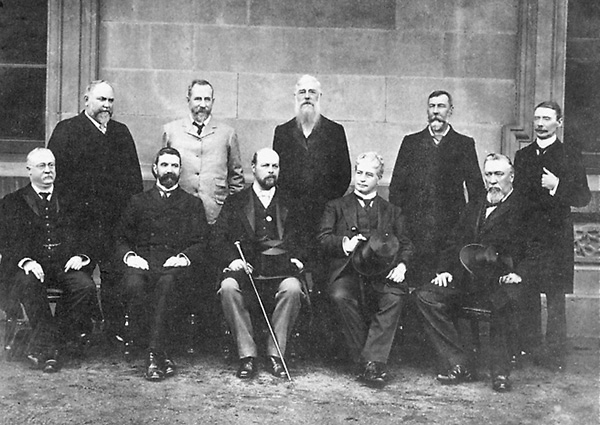

For decades many politicians and businessmen had been trying to convince the governments and the people of the six Australian colonies that federation would be a good thing. They believed that Australia needed a single national government to make decisions for all Australians. The colonies would become states within the Australian nation.

The two most important people in the federation movement were Henry Parkes and Alfred Deakin. Parkes came to Australia in the late 1830s. For many years he ran his own newspaper, The Empire, in Sydney. He was always a poor businessman and frequently ran out of money. But Parkes was a great politician. In 1899 in the little town of Tenterfield, New South Wales, he declared that the colonies should federate. By then he was an old man. Everyone knew him by his long beard and mane (грива) of white hair. He did not live to see the colonies federate. But for his early efforts Parkes became known as the ‘father of federation’.

Henry Parkes

Alfred Deakin came from Victoria. He was a highly intelligent man and a great speaker. He became the second Prime Minister of Australia (Edmund Barton was the first).

Alfred Deakin

One reason why Australians were keen to have a national government was their fear of invasion by Germany or some other rival of Britain’s. Australians began to feel that they could not go on relying on Britain to defend them. A single government was needed to plan the best way to defend the country’s coastline. Above all, they believed that Australia needed its own navy.

The people who wanted federation also said that the taxes put on goods passing between the colonies should be stopped. These taxes - tariffs - meant that everybody had to pay more for goods coming from other colonies. Federate the colonies, it was said, and food and many other items would be cheaper. Australians were also growing to believe that they had a lot in common whichever colony they came from. They liked the idea of Australia being one country with one government.

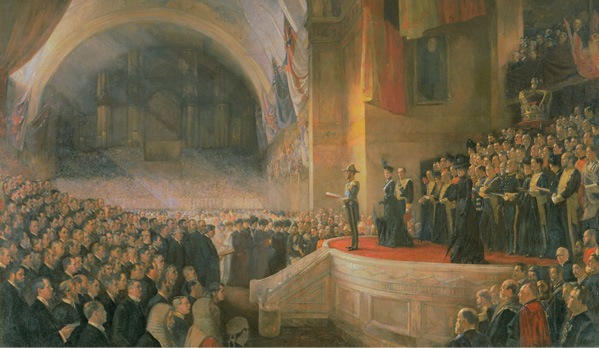

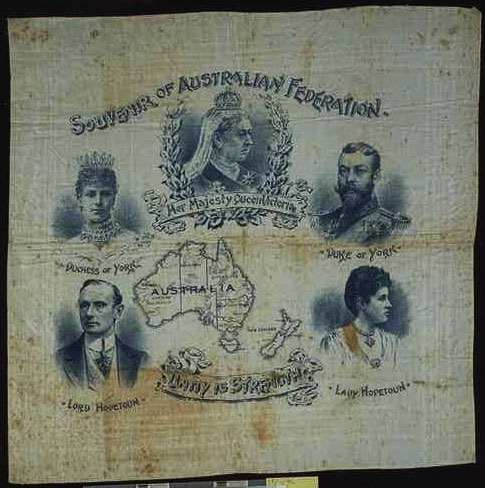

In 1899 the people of Australia voted in favour of federation. Elections were held for the parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. The Duke of York sailed out from England to declare on 1 January 1901 that the new nation had come into being. He opened parliament in Melbourne on 9 May 1901. Everywhere the new flag was flown. But the national anthem was the same as Britain’s. Australia was going to keep its loyal ties to Britain.

The opening of Parliament

The Commonwealth of Australia comes into being.

The first Federal Election is held. Edmund Barton becomes Australia’s first Prime Minister.

In 1911 the Australian Capital Territory was established for a new capital, Canberra.

The Australian Capital Territory

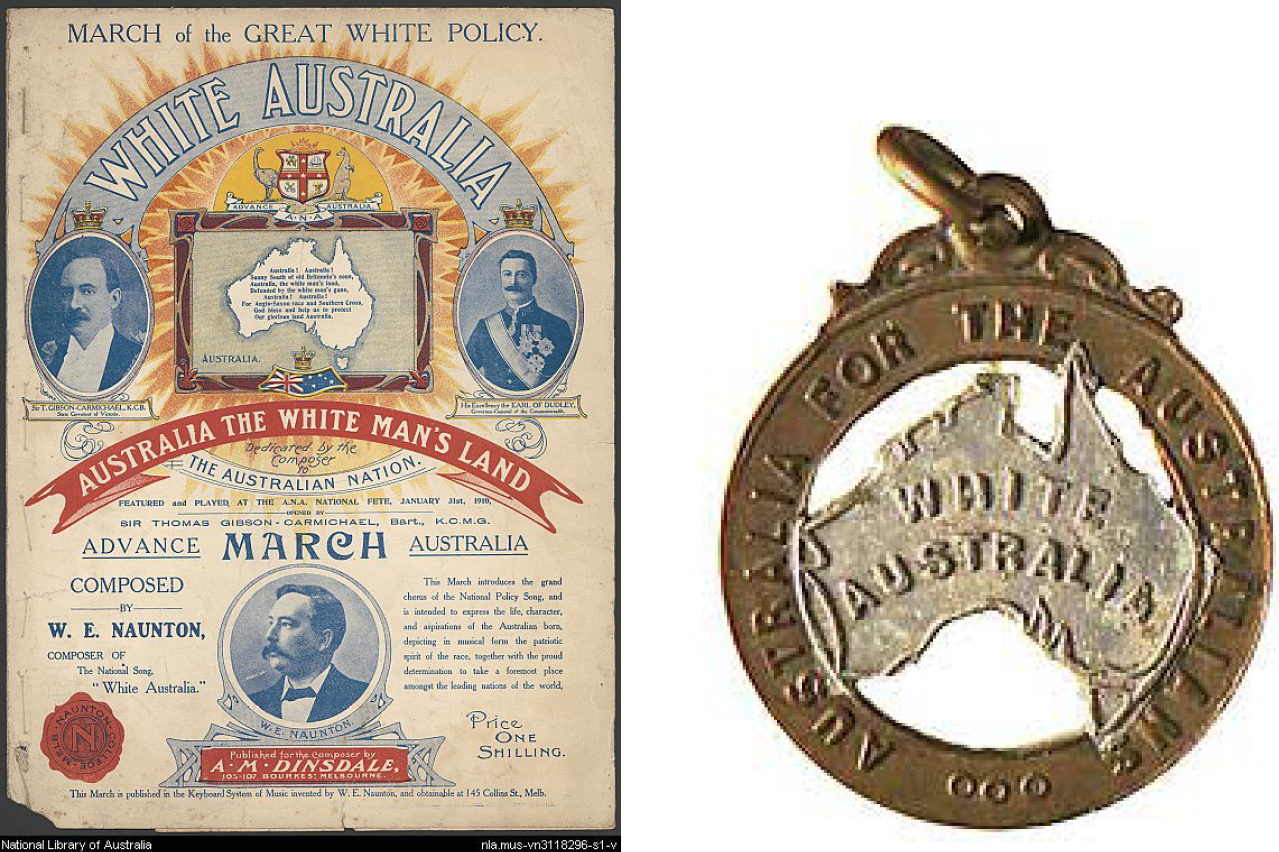

White Australia Policy

One of the first objectives of the new federal government, established in 1901, was the design of the White Australia Policy. The White Australia policy refers to an extensive period of both official and unofficial discrimination in Australian history, during which immigration policy and citizenship requirements were heavily biased to favour white European migrants, and more specifically Anglo-Saxon migrants over other races. Although in the present day Australia generally prides itself on being one of the most multicultural of the “western-style” democracies, its past contains a period of government-endorsed racism that is perhaps exceeded only by the apartheid regime of South Africa.

The policy can be traced back to the 1850s when violence against Chinese miners led to the colonial administration introducing restrictions on Chinese immigration. Towards the end of the 19th century the kanakas (the South-east Asians recruited to work in the sugar cane fields) were the main target of discrimination on economic grounds. Squatters, plantation owners and shipowners had occasionally introduced Asian workers because they were cheaper to employ. Australians feared that if this was allowed to happen on a large scale they would have to accept the same low wages or go without jobs altogether.

A lot of Australians believed that so long as there was more than one race in Australia there would be trouble. People of different races never could get on together, they said. The Aboriginal people no longer much concerned white Australians because they were convinced that they would soon die out. To allow any new race in would be madness, they said.

Alfred Deakin, a Victorian politician who was soon to become Prime Minister, said the main reason for the colonies agreeing to become one nation was to make the White Australia Policy an Australian law. All Australians, Deakin said, wanted to be ‘one people and remain one people without the admixture of other races’.

The White Australia Policy was to be like a fence around Australia’s shores.

In 1901, the new Federal Government, as its first act, passed the Immigration Restriction Act to “place certain restrictions on immigration and... for the removal... of prohibited immigrants”. The Immigration Restriction Act effectively ended all non-European immigration by providing for entrance examinations in European languages.

The Immigration Restriction Act of 1901 stated that immigration was prohibited for any ‘person who when asked to do so by an officer fails to write out at dictation ... a passage of fifty words in a European language dictated by the officer’. Not many Asians, it was soon discovered, had a good working knowledge of Bulgarian or the Transylvanian dialect of Romanian. In the words of a contemporary cartoon, “It isn’t the colour I object to, it’s the spelling.”

The Immigration Restriction Act effectively stopped all non-European immigration into the country and that contributed to the development of a racially insulated white society.

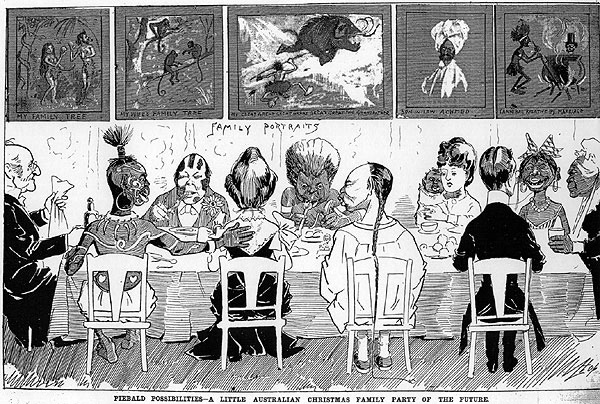

Cartoon: “A little Australian Christmas family party of the future”

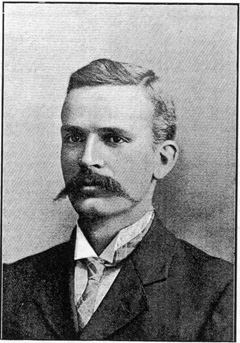

One of the most celebrated victims of the dictation test was Egon Kisch, a Czechoslovakian communist writer who arrived in Australia in 1934 aboard the liner Strathaird to address an anti-war congress.

Egon Kisch

The Australian government wanting to exclude Kisch on political grounds claimed that according to information received from the British authorities, he was an ‘undesirable visitor’ and could not therefore enter the country. When Kisch attempted to land in Melbourne he was promptly arrested and returned to his ship, but while the ship was travelling to Sydney, his friends took the case to court. The government was unable to produce its ‘information’, and Kisch was allowed to land.

Once ashore, Kisch was taken to a police station and given a dictation test. He could speak several European languages, but a test in the official’s version of Scottish Gaelic was beyond him. Once again he was arrested, prosecuted as an illegal immigrant and sentenced to six months’ jail. On appeal, the High Court ruled that Gaelic was not a European language within the meaning of the Act. Kisch was freed, given a second dictation test which he also failed, and was again declared an illegal immigrant.

The farce was brought to an end when the government agreed to stop further legal action and to pay Kisch’s court costs on condition that he agreed to leave the country. He finally did so in March 1935.

The policy was openly endorsed by both the government and general society during the first half of the 20th century. It was not until after World War II that attitudes began to change, though initially the change in social attitudes was less the result of a more “enlightened” viewpoint, but rather the result of an extreme labour shortage in the booming economy of the 1950s.

Identity forged by War

World War I (1914-1918), much more than federation itself, began the transformation of Australian life from that of six colonies to a united state aware of its new identity.

Early in the twentieth century Britain was still home for many people in Australia, even for some who had been born and raised in Australia. At school, children were taught that to be part of the British Empire was a privilege and a blessing, that to be British was to be noble and brave, and that loyalty to the Mother Country must never waver. Adults learnt much the same lessons from newspapers and books.

By 1910 a war between Britain and Germany seemed very likely. The British government told the Australian government that if war broke out in Europe Australia would be expected to send troops.

Australia began training its own soldiers. All boys from the ages of twelve to twenty-five were to be given military training. They had to put on a uniform and spend some of their weekends learning how to be soldiers. Some refused to obey the new law which they said should not be tolerated in a free country. Thousands were taken before the courts, and many went to jail. But most boys put up with it, and even enjoyed gaining the skills of warfare.

The war started in August 1914. That Australia would participate was not in question – it was constitutionally bound to follow Britain. The Australian Imperial Force (AIF) was formed whose members were all volunteers. The AIF would be commanded by British generals until the last year of the war. The new Australian Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher, announced that Australia would fight for Britain to ‘the last man and the last shilling”.

Prime Minister Andrew Fisher

For the great majority of Australians the war was a chance to show their love of England and prove themselves to the rest of the world. War was the best place for a man to prove himself - and the best place for a nation. An excited poet wrote:

A nation is never a nation

Worthy of pride or place

Till the mothers have sent their firstborn

To look death on the field in the face.

Young people rushed to join the army. It was like a great adventure. Some hurried because they feared the war would end before they got there. From the troopships the Australian soldiers wrote home to families and girifriends. Some said that it would have been unmanly not to go. Had they not joined up they could never have lived with their consciences - they could have never looked a girl in the face, they said.

Many Australian women encouraged men to go. Men who stayed home often received white feathers from women. A white feather was a way of saying ‘Coward’. Others joined simply because their mates had. A good many reckoned a soldier’s pay was better than the wages they were getting. For a lot it was a simple choice between the army and unemployment.

Responding to the allied call for troops, Australia sent more than 330,000 volunteers, who took part in some of the bloodiest battles. Suffering a casualty rate higher than that of many other participants, Australia became increasingly conscious of its contribution to the war effort.

At the end of 1914 the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (Anzac) was formed.

The Anzacs were employed in an attempt to knock Turkey out of the war. The idea was to force (захватить) the Dardanelles straights (проливы) at the eastern shore of the Mediterranean that opened to the Turkish capital. Once that was taken, the expeditionary force could enter the Black Sea and link with the Russian forces. It was first necessary to secure the Gallipoli peninsular, upon which Turkish troops commanded the straight.

In the early morning of 25 April 1915 British, French and Anzac forces made landings (высадка) on the peninsular. The Australians and New Zealanders scrambled ashore and stormed the slopes (склоны) before them. They dug in and defied (не поддаваться) all attempts to dislodge (вытеснить) them, but were unable to capture the heights despite repeated attempts to do so. With the onset (начало) of the winter, they abandoned Gallipoli and left behind 8000 dead.

The date of the fateful landing, April 25, 1915, became equated with Australia’s coming of age, and as Anzac Day it has remained the country’s most significant day of public homage (уважение, поклонение).

After their withdrawal from Gallipoli, the Australian divisions were deployed in the defence of France. Here they participated in the mass offensive against the German line during 1916 and 1917.

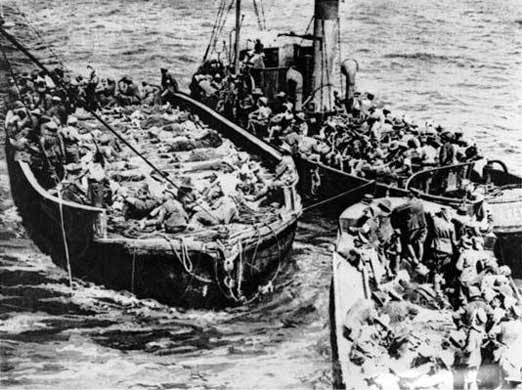

Evacuation of wounded troops from Gallipoli

Evacuation of all. Evacuation of allied troops from the beaches at Suvla Bay, Gallipoli. On 7, 8 and 9 January 1916 all troops were successfully evacuated. In every respect this was the best organized part of Operation Dardanelles.

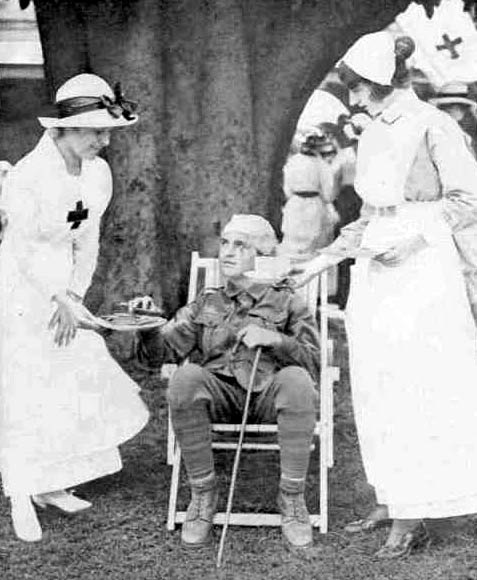

Coming home. A warm welcome for this young, wounded ANZAC soldier. He is met by nurses on arrival at a hospital in Randwick, Sydney, Australia

Gallipoli means so much to Australians as it was the first time this country, as an independent country, had fought in open warfare. It was obviously not a military victory, but in some way it became an Australian statement of nationhood.

During the First World War, out of a population of five million the armed forces voluntarily recruited 417,000 men, more than half of those who were eligible (годный). Of the 331,000 who served abroad, two out of every three were killed or wounded.

The soldiers had been promised great rewards for their service to the country. One of them was land. Land would be available to any soldier who wanted to become a farmer. Nearly 40 000 soldiers went on land.

The Effects of the First World War on Australia’s German-speakers

Prussia/Germany won the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and Germany became a new major power in Europe. There was a new patriotic feeling among Germans in Australia. The two Australian place names ‘Sedan’ (name of a battle in the Franco-Prussian War) and ‘Bismarck’ originate from this time.

The population of Australia in 1911 was 4,455,005. In Australia there were about 100,000 Germans in 1914. The First World War was a very difficult time for German-Australians. Before the War they were greatly respected. Between 1839 and 1914 German-Australians made a major contribution to Australia, particularly in South Australia (in 1900 almost 10% of the population of S.A. were German-Australians). Then Germany was the enemy in the War, and with the anti-German hysteria many British Australians forgot this large contribution, and believed that the Germans in Australia fully supported the German Kaiser. German-Australians were proud of their heritage and culture but politically they were completely for Australia. Most British Australians could not make this distinction. Many German Australians were in the Australian Army and fought and died for Australia. General John Monash was Australia’s most famous commander in the War, and he was the son of German-Jewish immigrants.

General John Monash

Some German Australians were interned (интернировать – ограничивать свободу гражданским лицам в период войны) whose families had lived in Australia for three generations. Employment became difficult for German-Australians, and as a result some went into internment camps voluntarily. During World War I, internment camps were set up in each state and the Australian Capital Territory.

Bourke, New South Wales (1915–18)

Bourke in far north-western New South Wales became the wartime residence for German families deported from the Straits Settlements (now Singapore and Malaysia), Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Fiji and Hong Kong, as well as some local internees. They were not housed in an enclosed camp as in other locations. Those who could afford it rented small cottages in the town, while others were accommodated in the jail and later in a disused hotel.

Internees inside the Bourke jail, 1915

Molonglo, Australian Capital Territory (1918–19)

The Molonglo camp was located outside Canberra. It was purpose-built late in the war in anticipation of the arrival of 5000 German and Austrian men, women and children from China and east Africa. These internees never arrived in Australia, so the German families interned at Bourke, New South Wales, were transferred there instead.

The Molonglo camp was the best equipped and least crowded of the World War l internment camps. It was closed in May 1919.

Blocks of barracks at the Molonglo camp

Some British Australians no longer wanted to work together with “Germans”. The mayor of Rainbow in Victoria’s Mallee region had to resign because he was German Australian. This happened to mayors elsewhere also.

German schools had to close. German was forbidden in government schools. The Premier of South Australia said that the Education Department must not employ anyone of German background or who had a German name. Most people had a negative attitude towards the German language. The Education Minister in New South Wales, Arthur Griffith, said on the 29th June 1915 in the NSW parliament:

“I might remark that we are at war with the German nation; we are not at war with German literature.”

In South Australia all 49 Lutheran schools were closed in 1917. After the winter break many of these were re-opened as state schools in the same buildings (rented by the Government from the congregations), with new teachers. This sudden change was traumatic for the youngest children particularly, as they couldn’t understand why the Government would want to do it. From then on, the students had no more German and Religion lessons.

Many Australians believed all propaganda lies about German Australia. Some German Australians were put into internment camps simply because an Australian (perhaps even a business rival) had said that the German Australian had said something negative about England, even if he hadn’t said it.

The nationalist fervour (пыл, страсть) of the time helped to increase the sales of Australian lager beer, as fewer imported German beers were sold, which had enjoyed a good reputation up until then. The Australian Brewer’s Journal wrote:

“The Teutonic brands which have been exported here by the enemy are taboo. Our lagers are equal if not better than their fancy brands.”

In 1916 the Upwey Progress Association (Melbourne) asked for a street lamp to be removed because it had the words “Made in Germany” on it.

St Kilda Football Club changed its colours in 1915 from red-white-black (same colours as the German imperial flag) to the black-gold-red of Belgium’s flag. St. Kilda reverted to the original colours later.

Many German Australians changed their name. Paul Schubert, teacher at Sturt Primary School in Adelaide, had to change his name in order to keep his job. He became Paul Stuart in 1916.

Even the British royal family needed to change its name. No longer Saxe-Coburg-Gotha; the new family name was Windsor. [Саксен-Кобург-Гота: династическое имя правящего королевского дома с 1902 по 1917 гг.; его носили Edward VII (правил с 1901 по 1910) и George V – правил с 1910 по 1936; последний во время 1-й мировой войны сменил его на династическое имя Windsor]

House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha

Governments in Australia changed very many German place names, despite the fact that these German names derived from “pioneers”. In South Australia the government changed 69 names of places and geographic features.

These prejudices did not exist only in Australia. In the USA ‘sauerkraut’ received the new name ‘liberty cabbage’ and ‘hamburgers’ received the new name ‘salisbury steaks’ (named after the doctor Dr. J.H. Salisbury: he recommended eating a burger three times daily). Sometimes these new names did not last.

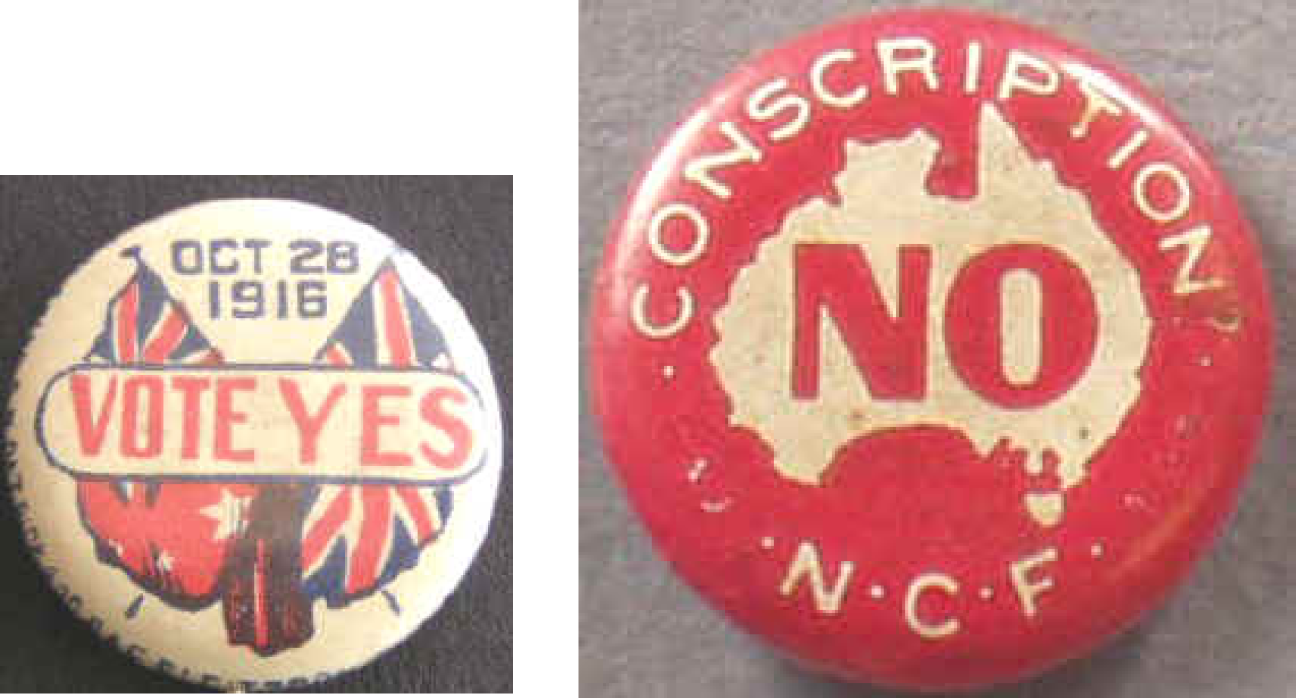

During the war the Australian Government tried to introduce conscription (призыв в армию). Australians rejected conscription in the first Conscription Referendum in October 1916. The referendum of 28 October 1916 asked Australians: Are you in favour of the Government having, in this grave emergency, the same compulsory powers over citizens in regard to requiring their military service, for the term of this War, outside the Commonwealth, as it now has in regard to military service within the Commonwealth?

“Patriots” blamed the failure of this referendum on Roman Catholics and German Australians. These “patriots” were sure that German-Australians had voted against conscription and that the large numbers of German-Australians must have affected the vote.

Pin back buttons supporting 1 side or the other in the 1916 conscription referendum

|

|

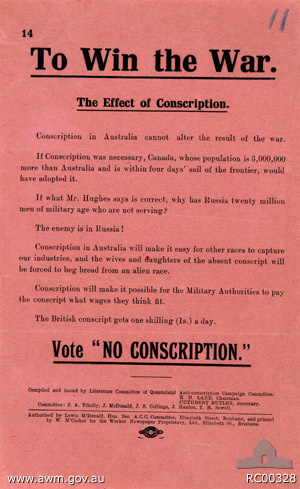

Colour leaflet against conscription. “To Win the War. The Effect of Conscription. Conscription in Australia cannot alter the result of the war. If Conscription was necessary, Canada, whose population is 3,000,000 more than Australia and is within four days’ sail of the frontier, would have adopted it. If what Mr. Hughes says is correct, why has Russia twenty million men of military age who are not serving? The enemy is in Russia! Conscription in Australia will make it easy for other races to capture our industries, and the wives and daughters of the absent conscript will be forced to beg bread from an alien race. Conscription will make it possible for the Military Authorities to pay the conscript what wages they think fit. The British conscript get one shilling (1s.) a day. Vote ‘NO CONSCRIPTION’. |

In 1917 Prime Minister Billy Hughes took away from German Australians the right to vote, however, the second Conscription Referendum held in December 1917 was also defeated.

Prime Minister Billy Hughes

In “The Australian People and the Great War”, Michael McKernan wrote that up until 1914 the German-Australians “had been admired and respected. But the Australians, so heavily committed to the war emotionally, needed to manufacture a war close at hand lest their knitting and their fund-raising be their only real war experience. The German-Australians became the scapegoats for Australia’s fanatical, innocent embrace of war.”

Between the wars

The war was still a terrible memory in the 1920s. Sixty thousand young men had not come back. There were cripples on the streets - former soldiers - to remind people what the battlefields had been like. There was a great pride in the achievements of the Anzacs, but also horror at the human losses. People wondered what it had all been for and looked for ways to forget an unhappy world.

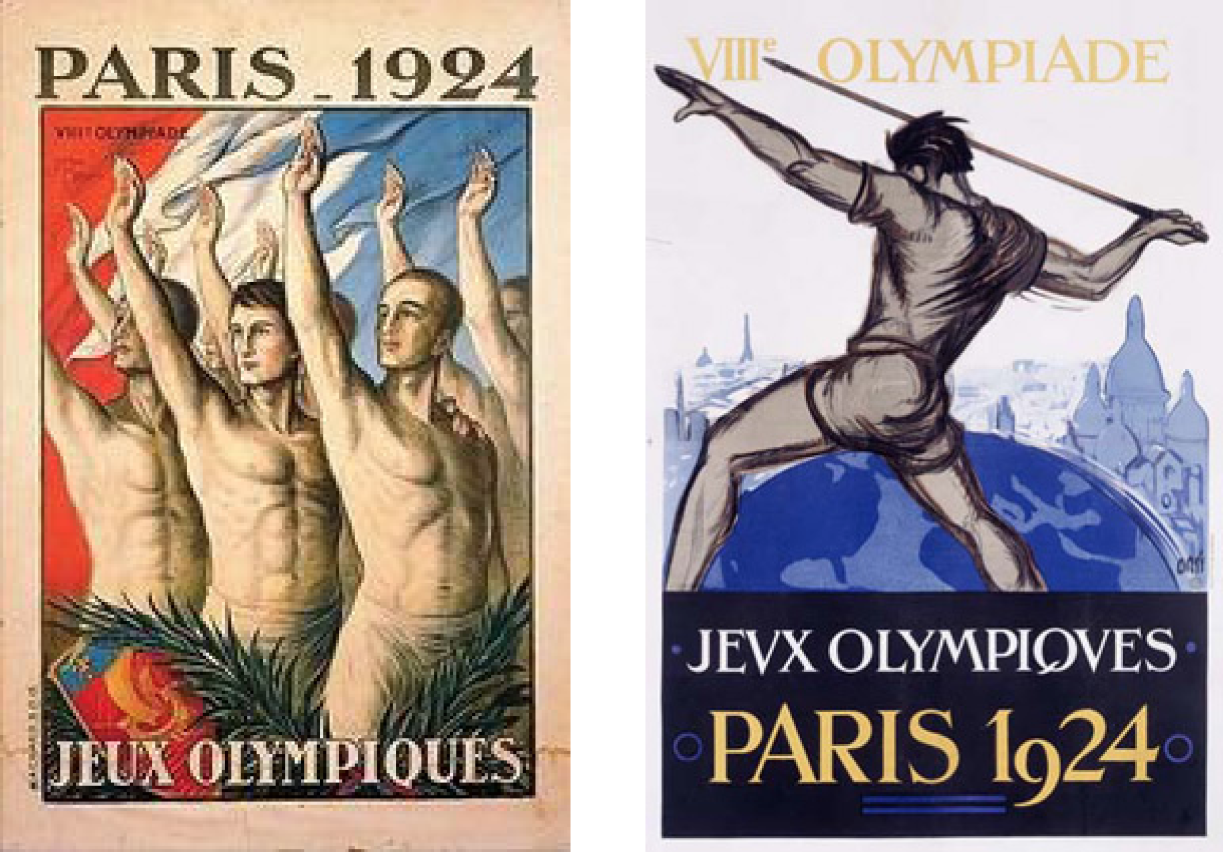

Sport helped. Cricket, tennis and football matches drew big crowds of spectators. When Australia won three gold medals at the Paris Olympics in 1924 the people at home marvelled at how such a new country could produce so many great athletes.

It was a great time for breaking records - in aeroplanes, motor cars and on bicycles. One man rode his bike from Sydney to Perth in just twenty-six days. Then two men made the journey by car in only six days. This was miraculous progress.

For well-off people in the cities there was an occasional opera or ballet to see. The most popular entertainment of all was probably dancing. Every community had at least one building which could be used for dancing. In the country, people rode into town, came by horse and buggy, to fox-trot the night away in a council or church hall. The men danced in special shoes called dancing pumps. The women wore shorter and shorter skirts and hair.

In the cities there were spacious and stylish dance halls, and ten or twelve piece bands. Increasingly they played music from America, especially jazz. For many people the 1920s was the jazz age. It was also the age of films. Australians liked to see films about their frontier history. The convict era and bushranging were favourite subjects. But soon Hollywood films were all the rage.

Work on the new federal capital at Canberra continued after the war. Parliament had selected the site in 1908, and construction had begun in 1913. The capital was transferred from Melbourne to Canberra in 1927.

Times had been hard for many people in the 1920s, but there had also been many signs of progress. The cities had grown. New roads and railways had been built for the new suburbs. Huge irrigation schemes commenced. People talked about Australia’s great future - ‘Australia Unlimited’ it was called.

The Great Depression

The Great Depression, the worldwide business slump (спад, кризис) of the 1930’s, had a disastrous effect on Australia’s economy. Australia was unable to sell its wool and wheat and metals overseas. Many wool, wheat, and sugar producers went bankrupt. In the worst of the depression, nearly a third of the country’s workers had no job. The Australian government was heavily in debt to Britain.

With no money people stopped buying goods. The factories that made the goods stopped producing so many, or closed down altogether. So more people lost their jobs.

By 1932 about one in every three Australian workers was unemployed, and in some places the number was even higher. Australia was in the grip of a depression.

Governments seemed unable to solve the problem. Many people offered suggestions. Some said “print more money”. Others said “print less”. Some said “give everyone free bread”. Some said “overthrow the rich and start a society like Russia”. Some said “pray”.

This is a photograph of over 1000 unemployed men marching in Perth,

Western Australia, to see Premier Sir James Mitchell

A small ‘dole’ (пособие по безработице) was paid to the unemployed but it was not enough to keep them - particularly if there was a family to feed. Soup kitchens were set up by local councils and the Salvation Army. Governments also established a system they called sustenance (поддержка). The workers called it “susso”. Unemployed people were given food and clothing in return for doing useful work, like building roads or clearing land. Not all the work was useful - much land they cleared grew back to bush within a few years. The workers who did ‘susso’ hated it. They felt that they were being treated as inferior citizens - rather like convict labour even though they had committed no crimes.

There were beggars in the streets. There were people with malnutrition, and skin diseases caused by bad diets. Long queues formed outside shops and factories every time a job was advertised. Occasionally there were street marches by unemployed people who wanted to show the world that something should be done.

A lot of men and women went to the country. It was called going ‘on the track’. These people wandered about in search of work by day and slept under the stars by night. There were often camps of unemployed people in country towns, as there were in the cities.

Some farmers and townspeople gave them jobs to do in return for food or a few shillings. Some who had no work to offer gave them food anyway.

There was not much farm machinery in the 1930s so farmers needed more workers at various times of the year. The unemployed could earn a little money in the countryside, following the harvests of hay, vegetables and fruit. Or they picked up jobs clearing farms of rubbish and cutting wood. And there were rabbits in the country - rabbits to be trapped. Rabbits provided a meal and their skins were worth a bit.

People suffered a great deal in many other ways. The depression ended the hopes of thousands of young people for a good education which would let them do the things they dreamed of. But Australians coped as best they could. They could not buy clothes or furniture or toys, so they made them. They could not buy much food so they grew what they could in their backyards and swapped (обмениваться) or shared it with neighbours.

They could not afford to pay much for their entertainment, so they went to football and cricket which were cheap. And they organized their own amusements - there were card nights, community singing, neighbourhood picnics and sports days.

World War II

When war came again in Europe in 1939, Australia dispatched its small armed forces to assist in Britain’s defense. Australia entered World War II on the side of Britain on Sept. 3, 1939. It sent troops to fight German forces in mainland Greece, Crete, and northern Africa.

After the Pacific war between Japan and the United States broke out in 1941 and Britain was unable to provide sufficient support for Australia’s defense, the government sought alliance with the United States. Until the liberation of the Philippines, U.S. General Douglas MacArthur and his staff used Australia for their base of operations.

During World War II, the Japanese flew sixty-four raids on Darwin and thirty-three raids on other targets in Northern Australia. Darwin, being the largest town in the north of Australia, was as a key defensive position against an aggressive Japan. Australia developed Darwin’s military ports and airfields, built coastal batteries and anti-aircraft guns and enlarged its garrison of troops. Darwin was a key port for the ships, planes and forces defending the Dutch East Indies, so the Japanese decided to attack Darwin to overcome these defences.

From the first raid on 19 February 1942 until the last on 12 November 1943, Australia and its allies lost about 900 people, 77 aircraft and several ships. Many military and civilian facilities were destroyed. The Japanese lost about 131 aircraft in total during the attacks.

The Japanese bombing of Darwin and northern Australia

By early March, Japanese troops had landed in New Guinea and were threatening to invade Australia. Again Australian industry was transformed by the needs of war. The economy was redirected toward manufacturing, and heavy industries ringed the capital cities.

About 925,000 men and about 65,000 women served in Australia’s armed forces during World War II. Over 29,000 Australians died in battle or as prisoners of war.

Australia, during World War II, had a population of 7,000,000. Almost 500,000 were engaged in munitions, or building roads or airfields, and over 1,000,000 joined the armed services.

Brisbane was home to one of the South-West Pacific’s major submarine bases during the war. About 60 United States Navy submarines were based at New Farm, and four British midget submarines were also, secretly, stationed there.

The postwar years

Beginning in 1946, thousands of immigrants were transported from eastern and southern Europe to the Australian suburbs. This migration rivaled the earlier transportation of convicts and made the Australian population more cosmopolitan.

Australia became a member of the United Nations (UN) in 1945 and began to play an increasingly active role in world affairs.

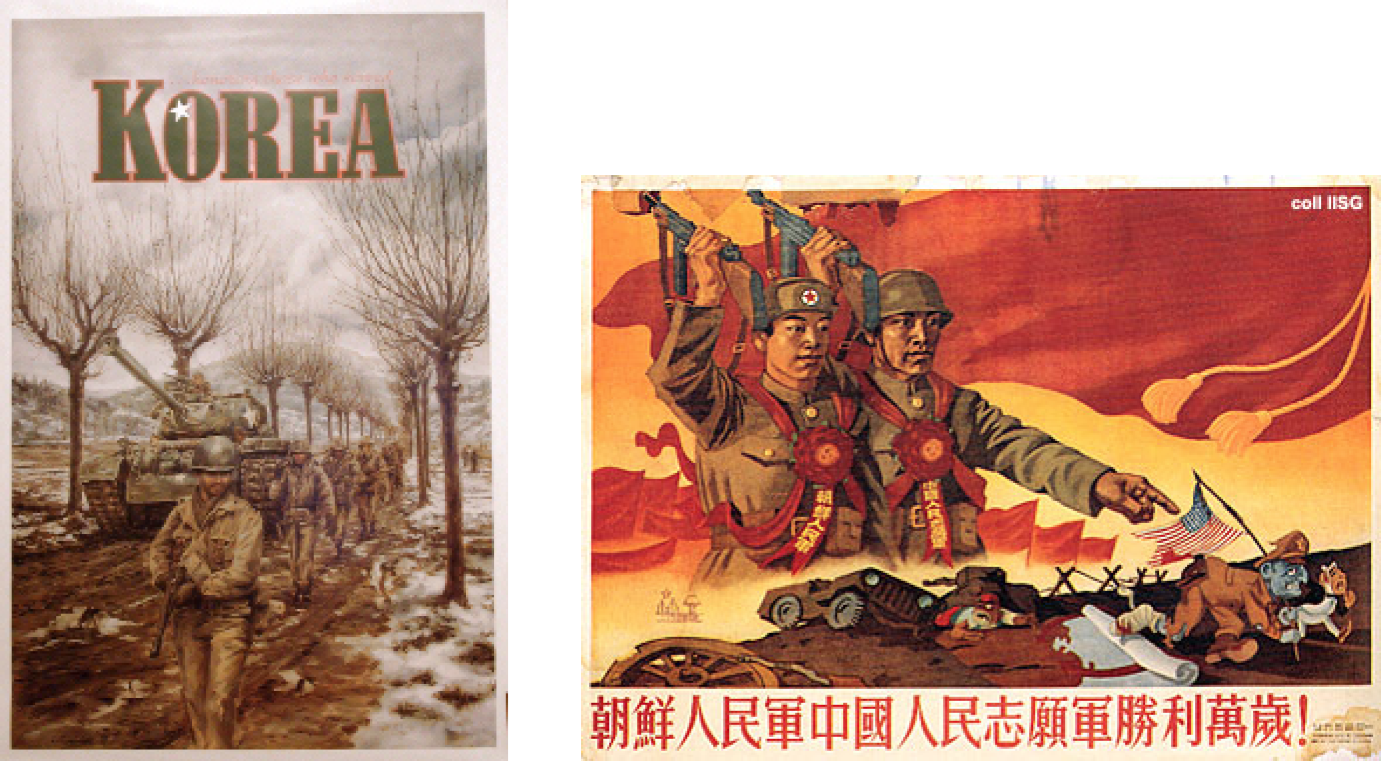

Militarily, Australia fulfilled its commitment to the Western alliance by fighting in the Korean War from 1950 to 1953, parti cipating in the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) from 1954 until its dissolution in 1977, and fighting in the Vietnam War as an ally of the United States (from 1964 to 1972).

Australia’s commitment to Vietnam began on the 3rd of August 1962 with 30 Military Advisors being sent to assist in training South Vietnamese Forces. Its commitment ended in June 1973 with the withdrawal of the last Australian Troops. The Vietnam War was the longest war Australia was ever involved in. Over 50,000 serving Australians, 520 Australian deaths, 2,400 wounded Australians and many more irrevocably changed lives is the human consequence of the Vietnam War.

The prosperity of the 1950s encouraged new efforts in education. Almost overnight the number of universities in each state increased threefold, the governments providing free university-level education to all those who were qualified.

During the 1960’s-1970’s. The White Australia policy was gradually discarded, and since the early 1970s the entry of immigrants has been based on criteria other than race.

The effective ‘death’ of the White Australia policy is usually dated to 1973 when a series of amendments prevented the enforcement of racial aspects of the immigration law. However it was not until the 1978 review of immigration law that racism was entirely removed from official policy. During the 1980s all forms of racial discrimination were made illegal in a series of anti-discrimination Acts.

In the 1960s, government and private attempts were made to integrate Aborigines socially and culturally, including granting them the right to vote in 1967. A national referendum in 1967 granted full citizenship to Aboriginal Australians.

Australia generally enjoyed economic growth and prosperity. It resulted chiefly from the discovery of vast mineral deposits in the 1950’s and 1960’s. The export of bauxite, coal, iron ore, and nickel added greatly to the country’s income.