Валерия Куватова

Москва, ИВ РАН

Valeria Kuvatova

Moscow, Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences

kintosha@mail.ru

Македонские и римские традиции погребального искусства

в живописи раннехристианских гробниц Фессалоники

В настоящем исследовании предпринята попытка проследить возможные истоки раннехристианского искусства Фессалоники и выявить непосредственные влияния основных художественных традиций региона – римской, местной и восточно-средиземноморской (Александрия и/или Малая Азия). Семиотический и контекстуальный анализ живописи фессалоникийских гробниц показал, что иконографические типы раннехристианских сюжетов заимствовались в искусстве Рима, в то время как композиционные принципы, орнаментальные мотивы и ритуальные сцены опирались на местную традицию. Светское искусство Римской империи также значительно повлияло на фессалоникийскую традицию погребальной живописи.

Ключевые слова: раннехристианское искусство, погребальное искусство, живопись гробниц, гробницы Салоники, раннехристианская живопись, живопись Македонии, древнеримская живопись

Despite the powerful Macedonian artistic tradition, the development of Early Christian funerary painting in Thessaloniki was strongly influenced by the Early Christian art of Rome, semantically the most advanced throughout the Late Roman Empire of the 3rd – 4th centuries. Scholars have a tendency either to derive Thessalonian funerary painting from the local artistic tradition or to categorize murals as having been produced by local workshops or workshops with Roman connections.

The contextual analysis of the extant monuments, though, speaks for a slightly different paradigm of the development of Thessalonian Early Christian funerary painting. The most reasonable way to point out the main impact vectors is to start with a study of figurative scenes. The iconography of the most popular Early Christian compositions had already attained a “canonic” form by the mid-3rd century. Any deviation from the mainstream iconographic type may serve as evidence of some impact other than Roman. Moreover, the intellectual approach to the elaboration of iconographic programs turned the Roman funerary monuments into semiotic texts, where the relationship between the scenes produces multiple connotations, enriching the semantic content of painting programs.313 In provincial funerary art, the semiotic approach towards the iconographic programs is less common and usually demonstrates some level of Roman influence.

The iconography of most depictions of biblical episodes in Thessalonian tombs corresponds to the mainstream Early Christian artistic tradition. Meanwhile, some iconographic nuances enlighten the origins of the particular iconographic types chosen by the artists.

E. Paneli attributes the paintings from tombs 15 (dated mid-3rd c.)314 and 49 (dated mid-4th c.)315 to a local workshop.316 She underlines the paintings’ poor quality and mistakes made in the Hellenistic spelling of biblical names. The scholar also considers the artists’ knowledge of the Early Christian iconography rather sketchy. Meanwhile, she believes the paintings of tomb 52 (dated to the third quarter of the 4th c.)317 are likely to have been produced by a Roman workshop.318 The inscriptions do testify that Thessalonian Christians were rather superficially acquainted with biblical iconography and the spelling of Old Testament names. No Roman Early Christian funerary monument contains inscriptions describing biblical episodes, while the biblical scenes in provincial tomb paintings and sarcophagus carvings are often accompanied by inscriptions. Whereas some compositions from tombs 15 and 49 deviate from mainstream iconography, others stick closely to the Roman “canonical” types.

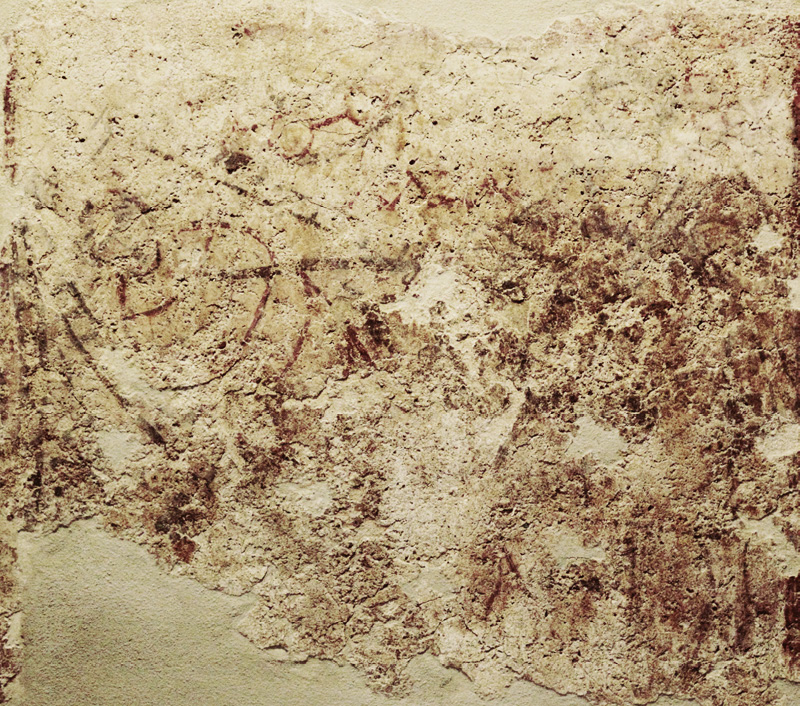

The episode with Daniel in the Lions’ Den is one of the most indicative in this respect. Daniel from tomb 15 is depicted naked (fig.1), while in tombs 49 and 52 he is dressed in a tunic or a chiton. Roman tradition always represents the prophet naked, as opposed to the provincial tendency to depict him dressed. Daniel is depicted dressed at such monuments, geographically close to Thessaloniki, as the Podgorica bowl319 (which is likely to have been made in Dalmatia), the Early Christian tomb from Pécs (Pannonia, modern Hungary) and the silver reliquary at the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, found in Macedonia. Thus, the Daniel scene from tomb 19 is a very uncommon example of mainstream Roman iconography in Eastern provinces. The Noah on the Ark episode from the same tomb also reproduces the conventional Roman iconographic types.

Fig. 1. Thessaloniki. Tomb 15. Western wall. Daniel in the Lions’ Den.

Thessaloniki, Museum of Byzantine Culture. Photo by author

The same tomb contains an unusual iconographic type of the Raising of Lazarus (fig.2). Lazarus is depicted lying down, instead of vertically put into his tomb. The only parallel is provided by a gold glass from the Vatican Museum (4th century320), depicting Lazarus lying on the stairs of his vertical tomb. Even more conspicuous is the iconography of the Healing of the Paralytic scene representing him either naked or wearing a breechcloth (which is unclear due to the poor state of preservation). Both the Roman and provincial traditions depict the Paralytic dressed in a short tunic.

Fig. 2. Thessaloniki. Tomb 15. Northern wall. Raising of Lazarus.

Photo by author

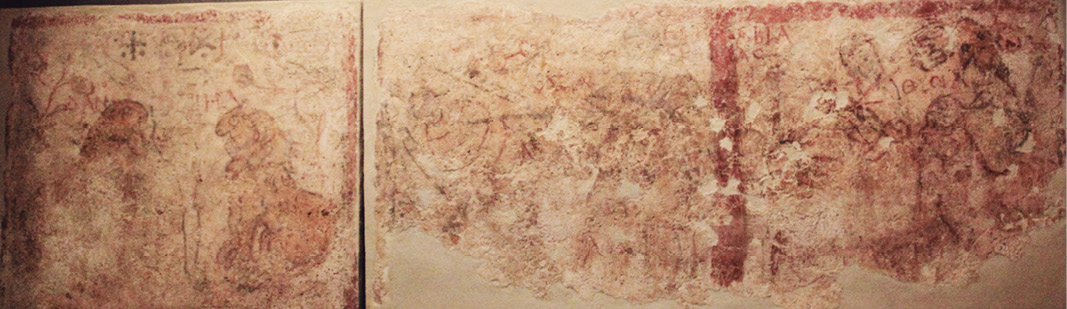

The elaborated iconographic program of tomb 15, inspiring semantically significant connotations, is also unusual for Thessaloniki. On the short walls two visually-similar scenes are skillfully counterpoised – The Good Shepherd between the two sheep and Daniel between the lions. All motion on the scenes of the long walls is aimed towards Christ the Good Shepherd (fig.3). This orientation most likely explains the features of the Sacrifice of Abraham scenes that alerted Paneli – the leftward turn of Abraham’s figure and the motion of his hand holding the knife, emulating Christ’s gesture in the Raising of Lazarus episode.321

Fig. 3. Thessaloniki. Tomb 15. Northern wall overview. Photo by author

The paintings of tomb 52, which Paneli considers to be the work of a Roman workshop, demonstrate the impressive artistic skill of their authors. However, the iconography of the Daniel scene corresponds to the provincial type, for the prophet is dressed in a tunic. Paneli compares the iconographic program of the tomb to that of 3rd century Roman sarcophagi,322 but the iconography and meaning of some episodes do not find parallels among the sarcophagus reliefs. While they do recall certain iconographic schemes, a number of features render their interpretation dubious.

One such scene is likely to depict a deceased person sitting on a chair with his wife standing by his side323 (fig.4). The other depicts a seated youth holding a book or scroll. E. Marki interprets this image as an idealized portrait of a philosopher and a Christian,324 while Paneli suggests that it may be connected to the iconography of the Evangelists.325 However, the distinсt iconographic type of the Evangelists developed somewhat later. As part of a funerary program, the scene may personify the virtue of learnedness, or portray one of the members of the family owning the tomb. The Roman late antique tradition provided typified portraits aimed to underline the social status and/or profession of the deceased. In the 3rd century the theme of learnedness gained huge popularity in Rome. However, the canonical depiction of a philosopher was not a youth, but a bearded man dressed in pallium. Roman funerary art also endued the portraits of deceased people with the various attributes of a typical philosopher. Anyway, even if these two scenes did go back to Roman traditions, they were adapted to the needs of the particular customer. In the meantime, the scene of the farewell of spouses is one of the most frequent in Greek funerary art, both on relief stelae and in vase painting. Thus, the composition with a sitting man and a standing woman may refer to this conventional funerary theme. The vase painting also provides some parallels to the scene with a reading youth (such as a lekythus at the National Archaeological Museum of Greece in Athens dated 4th c. BC). The two aforementioned scenes are not exact copies of either the Greek or the Roman iconographic type, and thus their iconography may derive from either tradition.

Fig. 4. Thessaloniki. Tomb 52. Northern wall. Reading youth. Thessaloniki,

Museum of Byzantine Culture. Photo by author

The interpretation of another composition from tomb 52 (a standing young man in a long dress with his hands outstretched, at the architectural background326) raises questions due to its poor state of preservation. Marki argues that it may be connected with some episode from the Old or New Testament, likely involving a purification ritual.327 Nothing in the iconography of the scene – as it has survived – supports the hypothesis of its connection to biblical subjects, but there is nothing that leads one to dismiss it either. In my opinion, the scene is reminiscent of the images of funerary rituals known from Macedonian stelae.

E. Paneli argues that the iconographic program of the tomb 52 was inspired by Roman sarcophagi of the 3rd century. She refers to the architectural background of some scenes (Daniel and a young man performing a ritual). While Marki assumes that this background goes back to the architecture of the Rotonda,328 Paneli believes it to be based on the architecture of the Colosseum.329 However, these architectural backgrounds are rather abstract, their sophisticated linearity speaking in favor of imagined (or painted) rather than real architectural prototypes. Such prototypes might have been present in Thessaloniki as mosaic decorations of early temples or secular buildings.

As was already mentioned, the semiotic approach to the development of iconographic programs always suggests the possibility of Roman influence. The choice and skillful juxtaposition and counterposition of scenes, as well as special iconographic instruments, contribute to the creation of multiple connotations and stress the meaning of every particular episode. The program of tomb 52 appears rather unimaginative in this respect. The semiotic approach appears only once – in counterpoising on the short walls of the two scenes bearing paradisiacal connotations (the Good Shepherd and Adam and Eve) and connecting them via the floral decoration of the vault (fig.5). The floral ornament enhances the paradisiacal connotations of both compositions. As for the other episodes of the program, their iconography and juxtaposition do not generate any semantic or visual interaction between them. Some of the figures face the Shepherd, while the figure of Moses striking the rock is turned in the opposite direction. Moses is depicted twice in the tomb (the second composition represents the prophet and the burning bush), but the two scenes do not interact within the program. The vita humana episodes are placed sporadically on the walls, with not obvious visual connection between them. Taking into consideration the provincial iconography of the Daniel in the Lions’ Den, it seems rather safe to suggest that the painters’ familiarity with particular iconographic types did not result from their being acquainted with Roman catacombs or sarcophagi. By the time tomb 52 was decorated (c. 360–370) 330 provincial art had already developed canonical iconography of its own, partially similar and partially different from the mainstream Roman tradition. This is also the reason why the paintings are missing inscriptions that form part of the iconographic programs of earlier tombs.

Fig. 5. Thessaloniki. Tomb 52. Overall view of the tomb. Photo by author

Another tomb containing biblical scenes (tomb 49) is dated back to the first half of the 4th century.331 The images are accompanied with inscriptions as in tomb 15, with the spelling of the Hellenistic biblical names being erroneous. They speak either of the authors’ uneasiness in handling the Bible or their lack of confidence in their own artistic skills, for the scene with Adam and Eve contains comments on the depiction of the tree (Δένδρον), the epigraphy to the composition with Noah in the Ark comprises an inscription to the image of the dove (Περιστερά) and the depiction of Daniel in the Lions’ Den has both lions inscribed (Λέων). Despite the overall mediocre quality of the painting, the iconography of the extant scenes turns out to be a combination of canonical models in some episodes, and experimental elements in others (as in tomb 15). The general scheme of the Sacrifice of Abraham strictly complies with the mainstream iconographic type, while the dress of Daniel – a long-sleeved long chiton – is very unusual for Early Christian art. As in tomb 15, the choice of episodes in tomb 49 is consistent with late 3rd–early 4th century Roman funerary art, apart from one surprising novelty. The short wall opposite to the image of the Good Shepherd is decorated with a scene depicting Saint Thecla in the bonfire and the figure of Christ to her right. The interpretation of the composition does not raise any doubts, for it contains the inscriptions Θέκλα, Χριστο[_] and Πυρ.

Such a choice of subject is unique for this region in this period. At the end of the 5th century the cult of St. Thecla gained ground in both the Eastern and Western Roman Empire.332 However, the interest in St. Thecla, and especially in this particular episode, in the mid-4th c. was not inspired by Roman art. There are no known 4th c. Roman funerary monuments. The Roman catacombs of Stt Thecla, dedicated to a local saint, lack depictions of Thecla from Ikonium. Bearing in mind the enormous popularity of the saint in Asia Minor, it seems logical to assume the respective influence vector. Meanwhile, another impact vector looks plausible: the only parallel to the Thessalonian scene is the depiction of the same episode of Thecla’s life from the so called Chapel of Exodus – an Early Christian mausoleum in the al-Bagawat necropolis, located in the southern Egyptian oasis of Kharga. The connections between Thessaloniki and Kharga can only be explained by the existence of a shared cultural power center – Alexandria. The narrative sources confirm the popularity of St. Thecla’s cult in the city: Athanasius of Alexandria in his first Letter to Virgins refers to the apocryphal Acts of Paul and Thecla.333 A number of the 4th and 5th century manuscripts of Acts were found in various places of Egypt.334 Thus, in addition to Macedonian and Roman traditions the Early Christian art in Thessaloniki was probably affected by Alexandrian or Asia Minor tradition. The particular iconography of the St. Thecla scene from tomb 15 could go back to the iconographic type of the Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace: the Saint is depicted standing in some sort of a furnace typical of Three Hebrews compositions, while the figure of Thecla in the Kharga mausoleum is put on the bonfire.

The lack of scenes of the Jonah cycle is the most striking in the Thessalonian funerary art. No extant iconographic program contains a depiction of Jonah. This is extremely unusual, for the episodes of the cycle are by far the most popular scenes of Early Christian art, abundant in Roman catacombs, sarcophagus reliefs, gold glass, reliquaries, red slip ware, clay lamps and other artistic objects. The failure to incorporate them into the tomb iconographic program adds weight to the idea that Thessalonian artists were not familiar with Roman wall paintings or sarcophagus carvings. It is likely that, at the beginning of the 4th century, they used pieces of applied arts as iconographic samples. This hypothesis explains the lack of Jonah depictions, as artifacts depicting scenes from the Jonah cycle would not have been available to the artists. However, the unavailability of iconographic samples does not equate to ignorance of Early Christian paradigms. The rebellious prophet’s popularity was not accidental, for his story alluded to baptism, resurrection, salvation and happy afterlife at the same time. Moreover, Jonah was one of the Early Christian symbols of Christ. Among other Old Testament characters, he was mentioned in the Roman 4th century prayer Ordo commendationis animae which obviously had its analogues in Thessaloniki. It seems improbable for Thessalonian Christians to ignore such a symbolic personage.

In fact, the decoration of tomb 41 is likely to demonstrate the way in which Thessalonian artists handled the lack of available iconographic samples of the Jonah theme for copying. On the short wall of the tomb, gourd fruits are depicted under a symbolic depiction of paradise (birds holding a red garland against a background of red flowers) (fig.6). The Early Christian cultural certainties closely linked the gourd to the Jonah story. However, tomb 41 is the only example of such a bold allusion to the prophet’s miraculous story. The closest parallel can be found in the 4th century gold glass from the Corning Museum of Glass,335 but there the gourd vine is depicted with a fish – a well-known symbol of Christ. All other extant images dedicated to the story of Jonah belong to the recognizable figurative iconographic types.

Fig. 6. Thessaloniki. Tomb 41. Southern wall. Gourd fruits.

Thessaloniki, Museum of Byzantine Culture. Photo by author

The hypothesis on the role of applied art pieces as samples for the Thessalonian artists explains the conspicuous difference between particular scenes of the same painted program in terms of their compliance with the mainstream iconographic types, which may have depended on the quality and availability of samples. The hypothesis also gives a reason for the obvious semiotic simplicity of the funerary iconographic programs. Their authors were not closely familiar with the Roman semiotic approach. As for the intellectual program of tomb 15, it could have been borrowed as a whole from an elaborate piece of applied art, such as, for example, the silver reliquary from the Thessalonian Museum of Byzantine Art (late 4th century).

While Roman art’s impact on the development of Thessalonian art was mostly confined to Early Christian subjects per se, the ornamental motives and compositional principles are likely to go back to the Greek artistic tradition. Attica used to be an important sarcophagus production center, but Attic sarcophagi were predominately decorated with Greek mythological scenes. B.C. Ewald underlines that iconographic programs of 3rd–4th century Attic sarcophagi lack some of the important themes of Roman sarcophagi, such as vita humana, vita felix and depictions of philosophers personifying learnedness. He connects this fact to the difference between the Greek (body-oriented) and Roman concepts of learnedness336. While more than 400 Roman sarcophagi contain depictions of pastoral landscapes (dating back to the period from 270 to 310337), they are completely lacking in the iconographic programs of extant Attic sarcophagi. Meanwhile, pastorals, ritual scenes and vita humana compositions were very popular in the Thessalonian Early Christian tombs. Thus, the influence of the Attic sarcophagus carvings on Thessalonian art – if any – was very insignificant. The impact of Macedonian funerary stelae reliefs or painting is more traceable, but Macedonian art had not been preserved in its Hellenistic shape. The ancient Macedonian artistic tradition developed under the influence of Roman art and thus impacted Early Christian art in both its Hellenistic and Greco-Roman forms.

E. Marki argues that interest in bucolic scenes increased in the Hellenistic period.338 In my opinion, Hellenism only witnessed the incorporation of some floral elements (bearing symbolic or ritual meaning) into funerary iconography - e.g. trees, often leafless, garlands, fantastic floral ornaments. The floral garland motif, in particular, turned out to be very persistent: it can be traced from Hellenistic through Christian times. However, landscapes and extended floral compositions entered funerary art somewhat later, following the development of the concept of Elysium. The funerary pastoral iconography was largely borrowed from secular art. As non-religious artistic traditions were very much alike throughout the Roman Empire, the funerary bucolic iconography also tended to universal schemes. Some popular motifs migrated from secular art to the pagan funerary context. Thus, the red flowers motif, initially known from the Pompeian lararia, first appeared in monumental tombs of Alexandria. Other secular painting motifs were likely to enter Early Christian funerary painting directly. In the 2nd–5th centuries mosaic art prospered enormously, demonstrating the considerable affinity of the figurative and ornamental motifs throughout the Roman Empire irrespective of the particular local mosaic schools. Floor mosaics often decorated public buildings and were available for studying and copying. The Thessalonian tomb 41 (dated 280–290339), for example, contains depictions of sea fauna – a popular motif among floor mosaics.340 Secular building painting decorations, such as stone veneer imitation, may also have migrated directly to Thessalonian tomb paintings.

Conclusions

It seems rather safe to suggest a few hypotheses in respect to the development of the Early Christian funerary art in Thessaloniki. In the late 3rd–early 4th centuries local artists borrowed the iconography of biblical episodes from Roman art, the first samples most likely being applied art pieces. In the course of adaptation, the Roman iconographic models changed, with this amended iconographic type becoming part of Macedonian funerary art. The non-biblical scenes, as well as the ornamental motifs, largely go back to local artistic tradition, both secular and funerary. The similitude of many iconographic elements of Thessalonian tomb paintings to the funerary painting of other regions results from the universal character of the Pax Romana cultural space.

Bibliography

Cimok 2000: Cimok, F. (ed.). Antioch Mosaics: A Corpus. Istanbul.

Davis 2011: Davis, S.J. The Cult of Saint Thecla. A Tradition of Women’s Piety in Late Antiquity. Oxford.

Ewald 2003: Ewald, B.C. Sarcophagi and Senators: the social History of Roman funerary art and its limits (review of Wrede H. Senatorische Sarkophage Roms…). JRA, 16, 561–571.

Ewald 2004: Ewald, B.C. Men, muscle, and myth. Attic sarcophagi in the cultural context of the Second Sophistic. In: B.E.Borg (ed.), Paideia: The World of the Second Sophistic. New York, 229–276.

Kuvatova 2015: Kuvatova, V. [Compositional Models of the Early Christian Catacomb Painting. Semiotic Analysis]. Filosofiya i kul’tura [Philosophy and Culture], Vol.III (87), 469–476.

Куватова, В. Композиционные модели живописи раннехристианских катакомб. Опыт семиотического анализа. Философия и культура, 3 (87), 469–476.

Marki 2005: Marki, E. [Representations of Fruits in Early Christian Art. The Case of Thessaloniki]. Deltion tis khristianikis arkhaioloyikis etairias [Deltion of the Christian Archaeological Society], 26, 85–92.

Μαρκη, Ε. Η Απεικόνιση των οπωρών στην παλαιχριστιανική τεχνή. Η περίπτωση της Θεσσαλονίκης. Δελτίον της χριστιανικής αρχαιολογικής εταιρείας, τόμος ΚΣΤ΄, 85–92.

Marki 2006: Marki, E. I Nekropoli tis Thessalonikis stous isteroromaikous kai palaiokhristianikous khronoths (mesa tou 3ou eos mesa tou 8ou ai. m. Kh.) [The necropolis of Thessaloniki in the Late Roman and Early Christian periods]. Athens.

Μαρκή Ε. Η Νεκρόπολη της Θεσσαλονίκης στους υστερορωμαïκούς και παλαιοχριστιανικούς χρόνοθς (μέσα του 3ου έως μέσα του 8ου αι. μ.Χ.). Αθπηνα: 2006

Paneli 2009: Paneli, E. [A New Interpretation of the Frescoes of Early Christian Tombs of Thessaloniki]. Vizantiaka [Byzantiaka], 28, 11–38.

Πανέλη Ε. Μια νέα προσπάθεια ερμηνείας και εικονογραφικής προσέγγισης τοιχογραφιών ταφικών μνημείων της Θεσσαλονίκης. Βυζαντιακά, 28, 11–38.

Pazaras 1981: Pazaras, O.Th. [Two Early Christian Tombs from Thessaloniki]. Makedonika [Makedonika], 21, 379–387.

Παζαράς, Ο.Θ. Δύο παλαιοχριστιανικί τάφοι της Θεσσαλονίκης. Μακεδονικά 21, 1981, 379–387.

Spier 2007: Spier, J. (ed.). Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art. New Haven.

313 Kuvatova 2015, 475.

314 Marki 2006, 215, sch. 67–72.

315 Marki 2006, 222, sch. 77–80.

316 Paneli 2009, 26.

317 Marki 2006, 223, fig.7–11.

318 Paneli 2009, 26–27.

319 In the State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. Spier 2007, 9, fig. 4.

320 Spier 2007, 223, fig. 50.

321 Paneli 2009, 24.

322 Paneli 2009, 26.

323 Marki 2006, 148.

324 Marki 2006, 152.

325 Paneli 2009, 16.

326 Marki 2006, 151, sch.89.

327 Marki 2006, 151.

328 Marki 2006, 152.

329 Paneli 2009, 15–16.

330 Marki 2006, 154.

331 Pazaras 1981, 380.

332 Davis 2011, 83.

333 See Περί παρθένιας ήτοι περί ασκέσιος; argumentation in Davis 2011, 89.

334 Davis 2011, 84–85.

335 Accession № 66.1.205.

336 Ewald 2004, 247–249.

337 Ewald 2004, 249; Ewald 2003, 569–570.

338 Marki 2005, 85–92.

339 Marki 2005, 221.

340 E.g. mosaic floor from Antakya, see Cimok 2000, 47–50.