Антонио Корсо

Афины, Итальянская археологическая школа

Antonio Corso

Athens, Italian School of Archaeology

antoniocorso@hotmail.com

Скульптуры пропилона тумулуса Каста близ Амфиполя

Статья является попыткой реконструкции скульптурной программы пропилона тумулуса Каста близ Амфиполя, датируемого временем около 320 г. до н.э. Декор сооружения включал ионийский рельефный фриз, фигуративные фронтоны и акротерии, а также две статуи, фланкировавшие вход. В статье анализируются и критически оцениваются все скульптурные элементы, которые на данный момент можно соотнести с комплексом пропилона. В целом программа доносит идеи гордости и прославления недавней победы Македонии над персами, а также содержит отсылки к легендарным событиям основания полиса божественными предками.

Ключевые слова: Амфиполь, Каста, Александр, Македония, Персия, пропилон, Диоскуры, Елена, Каллиопа, Рес

Acknowledgements

This research has been conducted together with Dr. Michalis Lefantzis. I am very indebted to this scholar for his advice, as well as his architectural competence. Thanks are also due to Dr. Katerina Peristeri and to the archaeological communities of Athens and Thessaloniki.

This article has been researched and written thanks to a grant provided by the Lord Marks Charitable Trust and channeled through the Benaki Museum. Thanks are due to Dr. Lady Marina Marks, president of this well-known charity, as well as to Prof. Angelos Delivorrias, Director of the Benaki Museum.

The Kasta Tumulus is a very large mound located north of Amphipolis, which was monumentalized in the late 4th century BC. At the top stood a lion, and a relief frieze ran at its base. At the base of the mound, facing south, were four rooms endowed with Sphinxes, female figural supports, a pebble mosaic showing the kidnapping of Kore by Hades and, finally, a painted frieze. This sequence of four rooms had two phases: in the first, it probably functioned as a heroon of Hephaestion, while in the second it became a manteion, probably administered by the famous seer Pythagoras of Amphipolis.123

The entrance to the tumulus took place through an Ionic propylon, distyle in antis. This entrance was endowed with statues at the sides of the gate.

A marble block from Amphipolis with a dedicatory epigram by Antigonus Kalla, hetairos of Alexander the Great, who achieved two victories in hoplitodromiai at Tyre124 at the time of Alexander’s conquest of the city, probably supported a bronze statue. The upper face of this block suggests that this block had a wall behind and other blocks to the viewer’s left and below. Thus, it supported a bronze statue in front of a wall, probably to the viewer’s left of a gate. Since the measurements of this block make it homogeneous with the corresponding dimensions of the blocks of the walls of room 1 of the Kasta Tumulus, it is likely that there was one statue at each side of the entrance. One of these two statues is probably preserved, and should be identified with the female draped marble statue found near Basilica no. 3 at the Acropolis of Amphipolis and kept at Kavala, Museum, no. Λ 607 (fig. 1).125 She may represent a priestess, a high ranking lady, or the goddess Nemesis, because her general style recalls the Nemesis of Agorakritos.126 If one of the first two possibilities is accepted, she may represent Olympiad. If the third hypothesis is endorsed, Nemesis would have symbolized the Macedonian victory over Persia, seen as retaliation after the Persian invasions of Greece in 490–479 BC. Since this statue is marble and the statue dedicated by Antigonus was bronze, it must have been set up at the viewer’s right of the gate.

Fig. 1. Statue from Amphipolis. Kavala, Archaeological Museum 607

The capture of Tyre by Alexander was thought to have been propitiated by Apollo (Diodorus 13. 108. 4–5), hence the dedication to a protagonist of that episode in a sacred space in which Apollo granted the power to predict the future may have been regarded as rather appropriate.

Statues at the sides of the gates of sanctuaries were typical of classical Athens: e.g. the Knights of Lykios stood at the sides of the Propylaea to the Akropolis of Athens, the Perseus of Myron and the boy of Lykios stood at the sides of the entrance to the Brauronion of the Akropolis, and the groups of Athena and Marsyas and of Theseus and the Minotaur stood at the sides of the propylon to the court in front of the west side of the Parthenon. Sometimes these statues were also dedicated by prominent private citizens, as was the case with the Knights and the boy of Lykios.127

Thus this dedication testifies to the continuity of this Athenian habit in late classical Amphipolis.

Concerning the external facade - distyle in antis with Ionic columns and a gate in the middle - architectural blocks found together with the lion and which had been wrongly attributed to the base of the lion probably should be attributed to this front, because their shapes and measurements are consistent with the masonry of room 1, and moreover, because they pertain to a construction in Ionic order, and thus cannot have been part of the base of the lion, which was endowed with Doric half columns. Facades of tombs showing the adoption of the Ionic order were trendy in Macedon in the late 4th century BC.128

It is likely that both the continuous Ionic frieze and the pediment of this facade were carved, because there are sculptures which can be attributed to these parts of the facade on the basis of their dimensions and style.

It is likely that two marble slabs currently in Istanbul once pertained to the frieze of the facade:

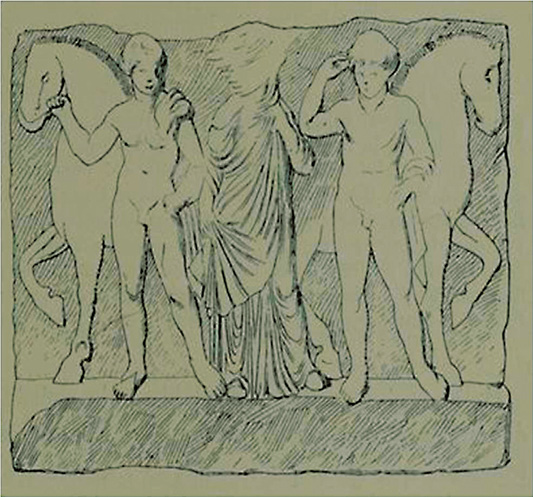

a. Slab no. 77 at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum (fig. 2)129, which represents two men with their horses behind them, standing in heraldic positions at the sides of a draped lady in full prospect. These two men, since they appear in their heroic nakedness, probably are the Dioscuri, thus related to Zeus, the supposed father of Alexander. They are emblematic of the knights who fought together with Alexander and Hephaestion to achieve the great, recent victory of their army. Of course, they are emblems of victory (for more about the Dioscuri as symbols of victory, see Diodorus 8. 32. 1–2). Their horses are so similar to the horse behind the hero with round shield in the frieze below the lion as to justify the attribution of these three horses to the same workshop. Thus, the lady in the middle is probably Helen, the heroine who was instrumental toward the sack of Troy. The popularity of the myth of Helen in Macedon in the late 4th century BC is evidenced by the pebble mosaic from Pella displaying the kidnapping of Helen by Theseus.130

Fig. 2. Relief slab. Istanbul, Archaeological Museum, no. 77.

Adopted from Mendel, 1914

The canon of the female body adopted for this figure is characterized by a short torso and long legs, and is the same as was adopted for the Korai in room 2 of the Tumulus. The drapery between the two legs of the heroine determines a concave configuration with curved folds and goes down to the ground and above the feet: these features are also found in the Korai of room 2. Even this lady may have been regarded as a mythical antecedent of the powerful woman who probably patronized the monument: Olympias, Alexander’s mother.

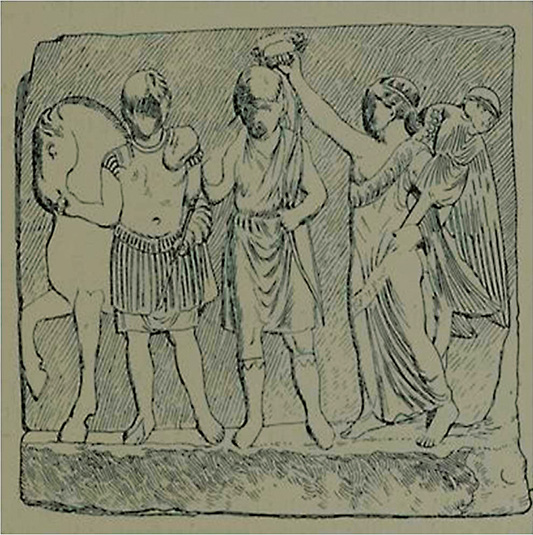

b. Slab no. 78 in the same museum (fig. 3).131 It also displays three figures: from the viewer’s left, a high official standing in front of his horse, then a goddess wearing short chiton and boots and holding a bow in her left hand, probably to be identified as Artemis, and finally a Nike holding a trophy in her left hand and crowning Artemis with her right hand. The official in this slab appears to be the same as shown in the frieze below the lion, and thus may also represent Hephaestion. The horse is also similar to the horse in the frieze below the lion, as well as to the two horses of the previously mentioned slab: in all of these examples, the rendering of the head, eyes and mane of the animal is basically the same.

Fig. 3. Relief slab. Istanbul, Archaeological Museum, no. 78.

Adopted from Mendel, 1914

Artemis with the bow is probably Artemis Brauronia,132 whose cult was probably of the highest possible importance at Amphipolis (see Antipater, Anthologia Graeca 7. 705): her iconography with a short chiton is indebted to the definition given to this goddess in Attica throughout the late 5th and 4th centuries BC.133

The Nike is endowed with long wings, similar to the wings of the Sphinxes of room 1. The strap across her chest and the concave configuration of the drapery with curved folds between her legs make this figure similar to the Korai of room 2.

The iconography of Nike, who crowns the tutelary goddess of Amphipolis, may be intended to exalt the crucial contributions of valuable men from this polis to the enterprise of Alexander.134 Nikai with the same attire, with long wings and about to outstretch a wreath with their left hands appear often in the coinage of Alexander the Great,135 and so this iconography may be a direct reference to a widespread pattern in royal propaganda.

Nikai holding wreaths will become traditional iconographic patterns in Amphipolitan imagery, and will continue to appear on the reverses of coins struck by this city in early Roman imperial times.136

Thus, this frieze may be intended to glorify the Amphipolitan leaders of the expedition of Alexander through the prism of mythology, i.e. their tutelary goddess as well as the Dioscuri and Helen.

The association of Artemis with Helen and the Dioscuri as depicted on this frieze may have been influenced by Euripides’ “Rhadamanthys”, where Artemis appeared and instructed Helen to establish rites to honour the dead Dioscuri (see the hypothesis of this tragedy). At a later point in this drama, Artemis declared that the daughters of Rhadamanthys had become goddesses, and that perhaps she may also have announced a similar destiny for the Dioscuri.

It is obvious that Euripides had a deep impact on Macedonian culture, since he spent his last years in the court of the Macedonian king Archelaus.

Thus, also in this frieze, perhaps Artemis is represented in her capacity to give immortality to another heroic dead, who in this case must be the young Macedonian official to her right.

Moreover, another marble fragment may have been pertinent to this frieze, because its dimensions and style are very similar to the two aforementioned slabs. This fragment was also found at Amphipolis, and is now kept at Kavala, The National Archaeological Museum, no. Λ 867.137 It depicts a young draped female with a girdle below her breasts. The back of this figure is flat and rough; thus, this sculpture is projected from a vertical slab.

One more marble slab should be placed in the same frieze. It also comes from Macedon, and is now at Copenhagen (fig. 4).138 Its pertinence to this frieze is proven by the height and the thickness of the slab, as well as the shapes of the upper and lower listels, the projection of the relief from its background and the style of the figures are identical to those features of the slabs at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. This slab depicts a tree with the usual coiled snake, which places the scene in a heroic sanctuary. Two boys are throwing stones at the tree, probably to coax the snake out. Two other boys are carrying a sick, old and bearded man on a stretcher in front of the tree with the snake. The bearded man is motioning to the snake with his right hand, probably in order to recover his health. The scene reveals that the heroon which it decorated was also endowed with healing functions. This slab, depicting a scene with movement to the viewer’s left, was probably on the right-hand side of the frieze.

Fig. 4. Relief slab. Copenhague, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, no. I. N. 2308

Other surviving marble slabs and figures may have been pertinent to the pediment of the facade.

There are three available fragments which were probably originally part of the pedimental composition:

a. Slab no. Ma 3582, bearing figures, in high relief, of a matronly lady and a girl, from Amphipolis, at the Louvre in Paris (fig. 5).139

Fig. 5. Relief slab. Paris, Louvre, DAGER, no. Ma 3582

b. Slab no. Ma 800, with figures in high relief, depicting a curved man resting on a stick and a seated woman holding a baby. This slab also comes from Amphipolis and is kept at the Louvre in Paris (fig. 6).140

Fig. 6. Relief slab. Paris, Louvre, DAGER, no. Ma 800

c. Sculpture no. Λ 335, in high relief, also from Amphipolis, kept at the National Archaeological Museum in Kavala.141 The schema of this figure depicts a Muse holding a lyre in her uplifted right hand, as in Mantinea.142 The back of this sculpture is flat and rough. This implies that it was a high relief figure projecting from a vertical slab.

These three fragments are stylistically similar and their dimensions are in keeping with their pertinence to the same pedimental composition.

In order to understand what has been depicted, we should begin with the only identification which appears to be highly probable: the Kavala scupture 335 is so similar to the Mantineian Muse with lyre as to even enable this figure to be identified as a Muse. She probably also held a lyre in her uplifted right hand. Therefore, the story depicted in this pediment probably had to do with Muses.

In the Louvre slab 3582, the matronly figure may be Mnemosyne, with a maid, attending the event taking place in the centre.

Finally the Louvre slab 800, because of its dimensions, must have been in the centre of the pediment, and thus probably conveys the crucial moment of the sacred story which was narrated in this part of the building.

The lady shown on this slab is also in high relief and is wearing chiton and himation. She seats on a klismos. The fact that she rests her feet on a footstool conveys the notion of the special importance of this figure. She holds an infant and has a man in front of her. The man is clearly the father of the infant. A himation wraps the lower part of his body, while his torso is bare. Since he is bent toward the woman and the infant, it is clear that the latter two figures are more important than him and are the central characters of the narration.

By analogy with statue 355 at Kavala, the young woman represented here must also be a Muse, and specifically one of the Muses who gave birth to a child. Since this composition was carved at Amphipolis, she is probably the Muse who bore Rhesus.143 This Muse was usually identified as Klio. Of course, the infant is Rhesus, while the man with a bare torso must be the father of Rhesus, i.e. the river Strymon.144 The advanced age of this man, as shown by his bent-over posture, his resting on a stick, and the weak rendering of his torso with light-dark modeling, are typical features of depictions of rivers.

Thus the pediment probably represented the birth of Rhesus, the hero who symbolized the mythical past of Amphipolis.

His father Strymon was with his mother: the caring attitude of this figure, pathetically bent toward the newborn child, is typical of the late classical age and reveals concern and affection, which is most famously depicted in Eirene with Ploutos by Kephisodotus the Elder.

The child receives the care of his mother and is also welcomed by her sisters, the other Muses. Mnemosyne, the mother of the Muses and the grandmother of the child, does not miss the event.

The re-use of one type of the Praxitelean Muses, known to us thanks to the slabs of Mantinea, in order to represent a Muse at Amphipolis in around 320 BC is noteworthy because it reveals the rise of a sense of great respect toward visual schemata which characterized renowned opera nobilia.

Thus, whoever approached the facade of the tumulus could see the birth of the most important mythological hero of this region from his divine parents.

This theme was in-keeping with the probability that bones believed to be those of Rhesus were preserved in room 4 of the tumulus.

These findings lead one to the conclusion that the Kasta Tumulus was seen as the monument (mnemeion) to Rhesus, which was located on a hill (epi lophou) at Amphipolis, according to Marsyas, FgrH 135–136, frg. 7. This early Hellenistic Macedonian historian specifies that the hieron of Klio lay before the monument of Rhesus: thus, the place sacred to the mother of Rhesus may be identified with this propylon. A late classical dedication of a woman to Klio, found north of the city (SEG 24, 586), strengthens this identification.145

Finally, the façade was probably also endowed with akroteria. A kneeling draped girl with a girdle below her breasts, from Amphipolis and kept at the National Archaeological Museum in Kavala (no. Λ 629)146 is probably a local Nymph whose style is very appropriate to the akroterion to the viewer’s left. She is crouching, like the Nymph who witnesses the Kidnapping of Persephone in the wall painting at Vergina. Even the crouching Nymph on our propylon is probably marveling at the sacred story narrated in the pediment.

The central akroterion has probably also been preserved, and is the anthemion found at Kasta, kept at the National Archaeological Museum of Kavala (no. Λ 319).147

This propylon with its sculptural display is in-keeping with the formal features of sacred architecture and sculptures of the so-called Ionian Renaissance, and conveys the messages of the holiness of the Kasta mound with the 4 rooms behind the entrance, the great recent victory reported by Macedon, as well as the pride of Amphipolis: this town contributed a lot to the victory and was endowed with a wealthy mythical tradition, as well as divine founders.

Bibliography

Caruso 2016: Caruso, A. Mouseia, Rome.

Corso 2004: Corso, A. The Art of Praxiteles, Rome.

Corso 2015: Corso, A. The Sculptures of the tumulus Kasta near Amphipolis, Journal of Intercultural and Interdisciplinar Archaeology, 2, 193–222.

Drougou 2016: Drougou, S. Vergina – Aigai: the Macedonian Tomb with Ionic Facade. In: D. Katsonopoulou, E. Partida (eds.), Φιλελλην. Essays presented to Stephen G. Miller, Athens, 335–350.

Damaskos 2013: Damaskos, D. [Catalog of Sculpture in the Archaeological Museum of Kavala] Katalogos glipton tou Arkhaioloyikou Mousiou Kavalas. Thessaloniki.

Δαμασκος 2013: Δαμασκος, Δ. Καταλογος γλυπτων του Αρχαιολογικου Μουσειου Καβαλας. Θεσσαλονικη.

DNO 2014: Der neue Overbeck, Berlin.

Despinis 2010: Despinis, G. [Artemis Brauronia]. Artemis Vravronia, Athens.

Δεσπινης 2010: Δεσπινης, Γ. Αρτεμις Βραυρωνια, Αθηνα.

Head 1879: Head, B.V. Catalogue of Greek Coins. Macedonia, etc. London.

Kalaitzi 2016: Kalaitzi, M. Figured Tombstones from Macedonia. Oxford.

Kaltsas, Despinis 2007: Kaltsas, N., Despinis, G. [Praxiteles] Praxitelis, Athina.

Καλτσας, Δεσπινης 2007: Καλτσας, Ν. and Δεσπινης, Γ. Πραξιτελης, Αθηνα.

Koukouli-Khrisanthaki 1971: Koukouli-Khrisanthaki, Kh. Agonistiki epigraphi ex Amphipoleos. Archaiologikon Deltion, 26A, 120–127.

Κουκουλη-Χρυσανθακη 1971: Κουκουλη-Χρυσανθακη, Χ. Αγωνιστικη επιγραφη εξ Αμφιπολεως. ΑΔ 26Α, 120–127.

Lazaridis 2014: Lazaridis, L. Amphipolis. Athens.

Λαζαριδης 2014: Λαζαριδης, Λ. Αμφιπολις. Αθηνα.

Lilimpaki 2011: Lilimpaki, M. [The Archaeological Museum of Pella] To arkhaioloyiko Mousio Pellas, Athina, 140–145

Λιλιμπακη 2011: Λιλιμπακη, Μ. Το αρχαιολογικο Μουσειο Πελλας, Αθηνα, 140–145.

Lorber 1990: Lorber, C.C. Amphipolis The Civic Coinage in Silver and Gold. Los Angeles.

Mendel 1914: Mendel, G. Catalogue des sculptures grecques, romaines et byzantines 2. Constantinople.

Moltesen 1995: Moltesen, M. Catalogue. Greece in the classical period. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. Copenhague.

Price 1990: Price, M.J. The Coinage in the Name of Alexander the Great. Zurich.

True 1997: True, M. Rhesos. In: LIMC 8, 1044–1047.

Walker 2015: Walker, H. J. The Twin Horse Gods. London.

Weiss 1994: Weiss, C. Strymon. In: LIMC 7, 814–817.

Captions

1. Statue at Kavala, Archaeological Museum Λ 607.

2. Slab at Istanbul Archaeology Museum, no. 77.

3. Slab at Istanbul Archaeology Museum, no. 78.

4. Slab at Copenhague, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, no. I. N. 2308.

5. Slab at Paris, Louvre, DAGER, no. Ma 3582.

6. Slab at Paris, Louvre, DAGER, no. Ma 800.

123 See Corso 2015, 193–222.

124 About this block and its inscription, see Koukouli-Khrisanthaki 1971, 120–127.

125 See Damaskos 2013, 40–41, no. 8, figs. 19–21.

126 See DNO 2014, nos. 1141–1154.

127 See DNO 2014, nos. 729–730; 734–735 and 1080–1083.

128 See Drougou 2016, 335–350.

129 See Mendel 1914, 2. 293–294, no. 572. About the standard association of Dioscuri with horses, see Walker 2015, 126–180.

130 See Lilimpaki 2011, 252–253.

131 See Mendel 1914, 2. 294–296, no. 573.

132 For the importance of the bow in the iconography of Artemis Brauronia, see Despinis 2010, 105–114, pl. 23.

133 This iconography of Artemis may have been introduced by Strongylion with his Artemis Soteira: see Corso 2004, 58–62.

134 One of Alexander’s eight squadrons of Companions’ Cavalry was Amphipolitan: see e.g. Lorber 1990, 62.

135 See Price 1991, 81.

136 See Head 1879, 51.

137 See Damaskos 2013, 71, no. 48.

138 Copenhague, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, no. I. N. 2308: see Moltesen 1995, 130–131, no. 67.

139 See Kalaitzi 2016, 251–252, no. 173.

140 See Kalaitzi 2016, 252, no. 174.

141 See Damaskos 2013, 42–43, no. 11.

142 See Kaltsas, Despinis 2007, 82–87.

143 About Rhesus as son of a Muse, see True 1997, 1044.

144 About the Euripidean version according to which Strymon was the father of Rhesus, see Weiss 1994, 814.

145 See Caruso 2016, 356.

146 See Damaskos 2013, 42, no. 10.

147 See Lazaridis 2014, fig. 88.